The scimitar cats are another extinct species of felines with large canine teeth. They were large, long-limbed animals, and they probably used their impressive teeth to kill and dismember large herbivorous mammals.

When did it become extinct?

The estimates for when the last scimitar cat became extinct vary between 10,000 and 13,000 years ago, but it is possible that they survived into more recent times.

Where did it live?

The remains of the scimitar cat have been found in North America, Eurasia, and Africa.

Thousands of years ago, the world was a dangerous place, what with the saber-toothed cats on the prowl—predators that must have surely been greatly feared by our ancestors. If fearsome saber-toothed cats were not enough, there were other species of powerful, large-fanged cats that stalked the earth at the same time, and among the most well-known of these are the scimitar cats.

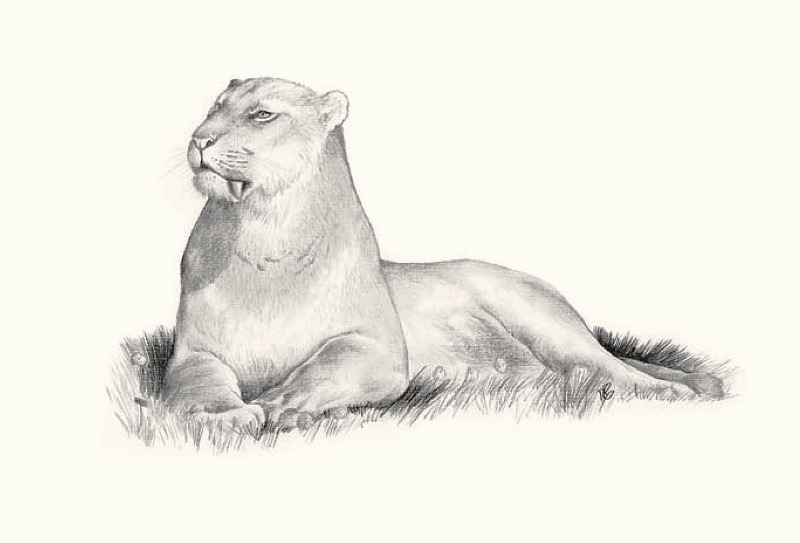

Fossils of scimitar cats are not as common as those of the saber-toothed cats, but the remains of 33 adults and kittens of one species (Homotherium serum) were found in a cave in Texas. Some of these skeletons were complete, giving us a good idea of what the scimitar cats looked like as well as throwing some light on how they lived. The scimitar cats were around the same size as a modern lion, with a stumpy tail; however, they were lightly built, with relatively long limbs.

Like the spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta), their forelegs were noticeably longer than their hind legs, and as a result, their backs sloped toward the rear. Although their forelegs were quite slender compared to the Smilodon saber-tooth cats, they were undoubtedly powerful and used to great effect when grappling with prey. As well as long limbs, the scimitar cat’s claws could be retracted as much as those of a modern-day tiger or lion.

The ability to retract their claws has important implications for the way these cats caught their prey, which will be covered in more depth later. The serrated canines of the scimitar cats were not as large as the massive daggers of the saber-tooth cats, but they were still impressive weapons. The European species, H. crenatidens, has the biggest canines of all the known scimitar cats. At around 100 mm, they dwarf those of an adult tiger, which are normally 55 to 60 mm long.

To protect these fangs, the mandible of the scimitar cat was massively developed, with flanges that acted like scabbards, probably to protect the canines. These scabbards were at their most impressive in H. crenatidens. Not only were the canines of scimitar cats fearsome, but their incisors were equally arresting. In H. crenatidens, the incisors undoubtedly formed an effective puncturing and grabbing mechanism that tore a lump of flesh from the unfortunate victim and were useful for carrying dismembered limbs.

What can the remains of the scimitar cats tell us about the way they lived? We know from where scimitar cat bones have been found that these predators probably migrated with the cyclical periods of cold and warm that have prevailed on earth for hundreds of thousands of years, and it is likely that they roamed the cold expanses and forests of the Northern Hemisphere.

We can assume that the conditions in which these animals survived are very similar to what we see in the Northern Hemisphere today. Much like the Siberian tiger, the scimitar cats were adapted to cold, temperate conditions. For camouflage, they may have had very pale, dappled fur, much like a lynx (Felis lynx) or bobcat (Lynx rufus). A large predator with dark fur in this environment would have stood out like a beacon, thus making it very difficult to approach wary prey. The long legs and the large nasal cavity of these cats have led some scientists to suggest that they could pursue their prey over long distances.

These felines were undoubtedly capable of short sprints, but it’s very unlikely that they were capable of long-distance pursuits. Like almost all other cats, the scimitar cats were probably ambush predators, using stealth to get within striking distance before launching a lightning attack. Interestingly, the structure of the scimitar cat’s rear suggests that they were not very good at leaping. The large nasal cavity probably also served to warm incoming air before it went into the lungs.

As the teeth of the scimitar cats are very different from those of the saber-tooth cats, it has been argued that the former had a distinct killing technique from that used by its bulky relative. With this said, we can never be sure how the scimitar cats caught their prey, but the amazing haul of bones discovered in Friesenhahn Cave, Texas, includes a huge number of bones from what could have been prey animals.

This unprecedented haul includes lots of milk teeth from more than 70 young mammoths. Could the scimitar cat have been a specialist predator of young mammoths? Based on observations of elephants, we know that youngsters aged between two and four years old will stray from the family group to satisfy their curiosity with the world around them. Isolated, they are vulnerable to attack from lions. It is possible that the scimitar cat was preying on similarly curious young mammoths and maybe even dismembering the carcasses before certain parts were taken back to the cave for consumption by the adults and cubs.

These mammoth remains may have been brought into the cave by other animals, such as dire wolves, the remains of which have also been found in this refuge; nevertheless, we are left with a tantalizing glimpse of how these long-dead cats may have lived. Perhaps they were specialist hunters of the young of the numerous elephantlike animals that once roamed the Northern Hemisphere.

-

The scimitar cats lived throughout Europe, North Africa, and Asia. There is also some fossil evidence that they reached South America.

-

The canine teeth of the scimitar cats appear to be adapted for slashing flesh rather than for stabbing, which was the tactic of the saber-tooth cat. When the scimitar cat’s mouth was closed around the throat of an unfortunate victim, the canines formed an effective trap along with the incisors. As the cat pulled back from the prey, it probably ripped out a sizeable chunk of skin, fat, and muscle, causing rapid blood loss.

-

Apart from the Friesenhahn Cave bones (discovered during the summers of 1949 and 1951), remains of the scimitar cat are relatively rare, and other finds are generally of a disjointed bone or two. The rarity of specimens suggests that the scimitar cats may have been quite uncommon, albeit widespread, predators that stalked the Northern Hemisphere up until the end of the ice age.

-

As with the last saber-toothed cats, we cannot be certain what caused the demise of the scimitar cats, but we cannot rule out the effect of humans hunting the prey of these animals, eventually depriving them of food.

-

The Pleistocene abounded with a variety of big cats, but today, there are only eight species of big feline. The Americas have lost all of their big cats except the cougar (Puma concolor ) and jaguar (Panthera onca ).

Scientific name: Homotherium sp.

Scientific classification:

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Mammalia

Order: Carnivora

Family: Felidae

Read More: American mastodon