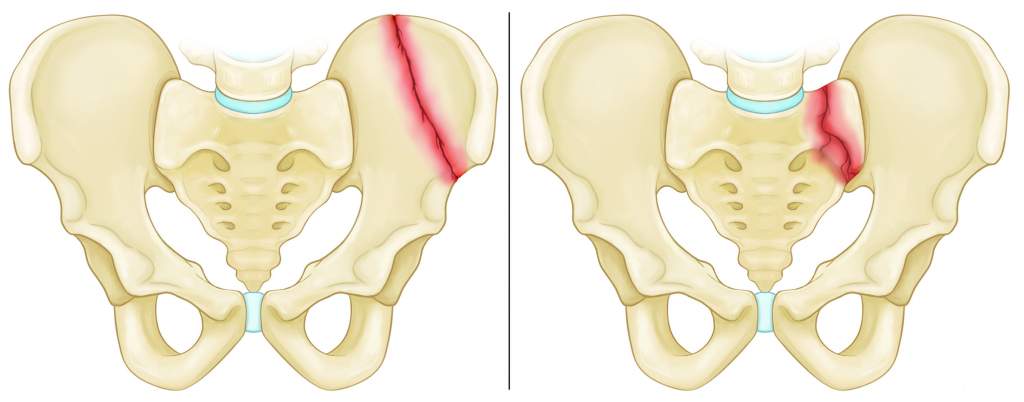

Dislocation or Fracture of the Pelvic Bone

-

There is a high mortality rate associated with pelvic fractures.

-

The majority of them are caused by motor vehicle accidents and falls from heights. Mortality and disability can be reduced through a multidisciplinary approach.

-

It is estimated that 3% of all fractures occur in the pelvic ring.

Injuries and their mechanisms

The cause of pelvic fractures can be attributed to four different patterns of injury. When the pelvic floor and anterior sacroiliac ligaments are ruptured as a result of anteroposterior compression, the hemipelvis is externally rotated and the pelvic floor is ruptured. Compression fractures of the sacrum can occur when the posterior sacroiliac ligament complex is disrupted by lateral compression. The intact sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments limit the amount of instability.

When the contralateral hemipelvis is pushed externally in a high-energy lateral compression injury, as in a rollover or crush injury, this can result in rotation of the contralateral hemipelvis. Motorcycle accidents often result in combined external rotation and abduction, which deforms the femur. Falling from heights produces the fourth pattern of shear force vectors, where an unpredictable degree of translational instability occurs.

Findings in Clinical Trials

During the physical examination, the skin, the perineum, and the rectum are examined to determine the injury mechanism and estimate the outcome. It is important to identify closed degloving injuries (Morel-Lavallée) in a proper way.

In order to find out the origin of the pain, it is necessary to palpate the bony landmarks of the pelvis, including the sacrum and the sacroiliac joint. Although excessive manipulation can increase bleeding by mobilizing the initial clotting, a single anteroposterior or lateral iliac wing compression maneuver should be performed in hemodynamically unstable patients.

For the identification of open fractures, a recto-vaginal examination is mandatory in all cases. Fracture hematomas are contaminated by bone spikes that protrude from the mucosa. Also, a thorough neurologic examination should be performed to determine whether there are any associated injuries including lower urinary tract injuries and distal vascular status.

The pelvic ring is evaluated as a possible cause of shock using an initial AP pelvic radiograph according to ATLS protocol. The patient should undergo AP pelvis radiography after successful resuscitation.

An inlet and outlet view, as well as an obturator or iliac oblique view, should be performed as soon as the patient is hemodynamically stable. Under general anesthesia, stress views can also be used to determine the actual displacement of the symphysis pubis. In order to determine the fracture pattern in greater detail, a CT scan is necessary.

Pelvic Treatment

An orthopedic surgeon usually treats stable pelvis fractures with nonsurgical treatment. These low-energy fractures usually require no surgery. An approach that is multidisciplinary and systemic is required for the management of unstable pelvic injuries. It is therefore imperative that the ATLS protocol is followed when the patient is hemodynamically unstable. In most cases, death due to pelvic fractures is caused by hemorrhage and shock.

In order to have a successful outcome, it is important to identify a significant pelvic injury, contact a physician as soon as possible, provide rapid resuscitation, control hemorrhage (using angiography or pelvic packing), assess and treat associated injuries, and offer mechanical stabilization when necessary. The first step of resuscitation should be to administer 2 L of crystalloid, followed by fresh frozen plasma, packed blood cells, and platelets in a 1:1:4 ratio.

Stabilizing an unstable pelvis temporarily can be accomplished by using a pelvic binder or sheet. A pelvic clamp or anterior external fixator should be applied after chest and spine radiography has ruled out other sources of bleeding. Trauma centers should follow their protocols when it comes to pelvic packing and/or arterial angiography.

Upon stabilization of the patient’s hemodynamic status, it is necessary to determine whether to perform a permanent mechanical fixation of the pelvis or a temporary fixation. A vertically unstable fracture can potentially increase the displacement of the fractured pelvis if anterior fixation involves anterior plating of the pubic symphysis or retaining the external fixation device in place. However, anterior fixation may provide posterior stability and can reduce displaced motion.

Seating stresses are normally absorbed, but weight-bearing stresses are not, and further internal fixation is often needed. It is usually deferred for a later date to perform posterior fixation (either surgically or percutaneously guided by CT scans). Surgical intervention should be made as early as possible in pelvic fractures affecting 2–4 percent of all pelvic fractures.

It is estimated that 72 percent of open pelvic fractures are grade III and need to be treated appropriately. An open pelvic fracture’s definitive stabilization method remains controversial. There is no need to worry about gross contamination when doing an internal fixation. In the event that contamination is present fecal or environmental, external fixation is preferable. In the event that fecal contents are in contact with the open wound, colostomies are recommended.