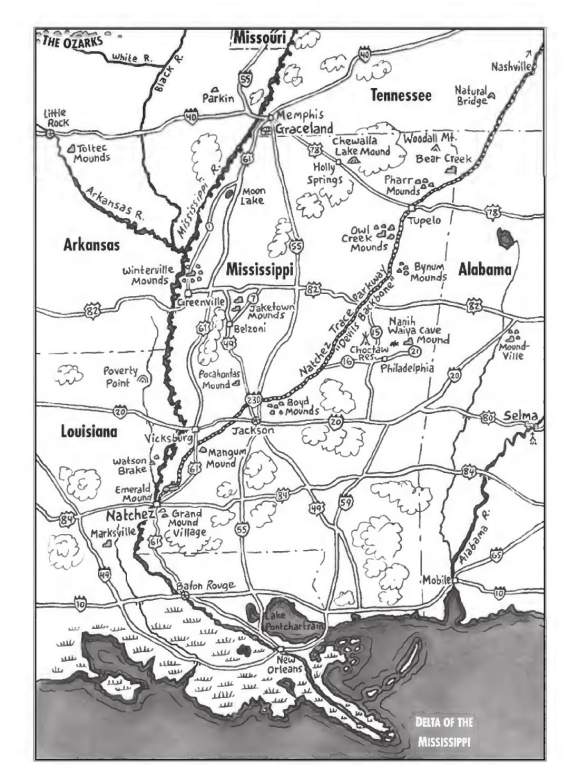

The prehistoric Natchez Trace, named by French traders and meaning “Natchez Indian Trail,” runs across Mississippi and Alabama before entering Tennessee. The 440-mile, (708-kilometer-long) pathway was opened by Archaic Indians over 8,000 years ago. The various mound-building cultures of the South, including the Woodland Indians, have continuously used the trail for thousands of years. Early Christian missionaries called it the “Devil’s Backbone” because of the importance Native Americans placed upon its use. European traders and trappers trampled down the rough road to settle the “Old Southwest.”

The state of Mississippi began to take on a modern appearance, largely due to the access provided by the Natchez Trace. From 1800 to 1820, the frontier brimmed with trade and new settlements, and the Natchez Trace became the busiest byway in the South. Today’s modern Parkway closely follows the original trail, with markers of important sites along the way. Natchez The last documented earthen temple mound builders were the prehistoric Natchez of the lower Mississippi River Valley.

The French observed that the residents of ancient Natchez were “devout sun worshipers.” Each of their seven villages had its own mound, but the group as a whole was focused on the larger Emerald Mound. The elaborate Emerald Mound was a truncated mound with terraced altars and temples on several levels below a dominant temple at the highest level. All the flat-topped mounds of Natchez contained individual thatched roof buildings, upon which effigies of birds or other symbols were placed. Arts and crafts flourished immediately before the abrupt decline of the Mississippians. The Natchez practiced a religion based on the solar disc, similar to the Toltec, Aztec, and Inca peoples of Central and South America.

Their chief was known as the Great Sun, and his relatives were called Little Suns and stood in the noble rank above the commoners. “Honored men” were those within the commoner rank, a class open to anyone who distinguished himself in war or religious devotion. Membership in the “Sun” family was defined by female-line inheritance or matrilineal kinship. The Great Sun governed the tribe with the help of his relatives, who held tribal offices, and through his knowledge of tribal politics.

Like the priest-kings of comparable Central American societies, the Great Sun was worshipped as a divine possessor of solar energy. The Emerald Mound crowning the ancient city of Natchez is the second largest temple mound of its kind in North America. Those people who belonged to the Mississippian culture became expert farmers and organizers. Populations grew tremendously large around ceremonial centers, and between harvesting seasons, huge earthen pyramids were constructed by hundreds of workers who moved vast amounts of dirt in thatch baskets.

Sometimes 20 or more mounds marked a ceremonial site. It is estimated that a phenomenal 57.3 million people lived in the Americas when Columbus arrived in 1492. The Mississippian people were known practitioners of human sacrifice, but their religious ceremonies surrounding it, if any, are unknown. Sacrifices were possibly made to conserve resources for the elite, eliminate captured enemies, or follow the grisly killing practices of their Toltec and Aztec contacts in Central America.

Human sacrifice, as practiced by the Natchez mound builders, was quite different from that practiced by the Aztecs or any other Mexican group. Upon the death of a chief, those people who had served the chief in life were expected to continue to serve him in death. Members of the Great Sun’s court were killed during his funeral so that they could accompany him into the next life. As such, those prehistoric Indians known to have performed human sacrifices are called the “Southern Death Cult” or the “Buzzard’s Cult.” The first modern European explorer to march through the South was Hernando De Soto in 1539–1542, on his unsuccessful quest to find gold.

The De Soto Expedition failed miserably in its efforts to duplicate the success of similar conquests in Mexico and Peru. On the long overland journey from the Florida Gulf Coast to Georgia, north to what is today Memphis, Tennessee, and then west to the Arkansas Ozarks, the De Soto Expedition came across some mound builder sites abandoned only recently. When the expedition arrived at any inhabited Indian settlement, they demanded enormous quantities of food for hundreds of soldiers and slaves, 200 horses, and their livestock. Surprisingly, he and his band of Spaniards came across Natchez while it was occupied and still under construction.

They called it Quigualtum, which may include a string of provincial settlements extending north into the Yazoo River Basin. De Soto did view some of the densely populated mound cities lining the lower Mississippi, but since riches were not to be found, the conquistadors continued traveling in their circuitous trail of destruction. The weary party reached Quigualtum near the end of their disastrous three-year campaign.

De Soto died in the spring of 1542, either in the vicinity of Natchez or near the mouth of the Arkansas River. They were confronted by the sheer numbers of angry Indians determined to fight back. The remnants of De Soto’s battered army left everything behind in a hasty retreat to Florida via homemade rafts. One of the last things the De Soto survivors noted about the Natchez Indians was their instant slaughter of the abandoned Spanish horses, butchering the animals for meat rather than keeping them as beasts of burden. It would be a long time before Europeans again reached the Mississippi Valley.

Most of the powerful mound-building societies were still largely intact when Columbus reached the New World in 1492, and their hasty demise is directly attributed to the spread of foreign diseases that came with the earliest European explorers. The Mississippian mound cities were abandoned and all but forgotten by the Woodland Indians, who moved into the region centuries later. By the time French explorers came down the Mississippi in 1673, almost all of the large Indian cities had vanished, largely due to continued Eurasian microbes spreading across the continent.

Natchez Trace, however, was still a functioning society when the French arrived. It is surmised that the majority of the Mississippian culture died off in devastating epidemics of smallpox, measles, tuberculosis, and the common cold. Thus, the De Soto Expedition contributed less to the mound-building societies’ direct downfall than the earlier Spanish conquests of the Aztec and Inca empires, yet Eurasian germs, particularly smallpox, did the real destruction. In some cases, the deadly microbes spread up the southern Mississippi Valley in advance of the Spaniards themselves.

Getting to Modern Natchez is a small city on the Mississippi River, but the Natchez mound builders lived in villages along Saint Catherine’s Creek outside the modern city limits. The place the French called “The Grand Village of the Natchez Indians” is located in the town of Natchez at 400 Jefferson Davis Blvd., just off Highway 61. The Emerald Mound site is located 10 miles (16 km) north of Natchez off Highway 61. There are other Natchez-related sites near Tupelo.

Read More: The Distinctive Pilot Mountain NC, United States