Page Contents

The Blackbird is one of the most familiar and best-loved garden birds. It is often regarded as uninteresting because of its very familiarity. In fact, because it is so easy to study, more is known of its lifestyle than of almost any other bird.

The blackbird, a bird familiar to everyone, is a successful and adaptable species whose natural habitats before man started to make his mark on the British countryside several thousand years ago. The birds were woodland edges and natural clearings. Now it not only frequents gardens in town and countryside but also most of the hedges over the millions of acres of British farmland.

The blackbird’s very numbers allow it to be studied in much greater detail than most species; thousands are ringed each year and nest recorders are able to find and record nests in great quantities Male, female, and juvenile. The adult male is quite literally a ‘blackbird’, with a wholly black plumage relieved only by a bright orange bill and an orange eye ring.

The younger males hatched the previous summer. retain their old flight feathers and some wing coverts, giving their wings a peculiar ‘patchwork’ effect where the old brown juvenile feathers contrast with the newer ones grown during the post-juvenile molt in their first autumn. The females are much browner, with a pale throat and speckling on the breast. Juvenile birds of both sexes have rich brown centers to many of their body feathers, but these are retained only for a month or two.

Territorial Song and Combat

The blackbird’s year, in Britain, may be said to start in February when the singing males begin to define their territories for the coming breeding season. This is not only accomplished through the exceptionally melodious medium of their song-used by the birds to announce their presence and continuing occupation of their territories but also by physical displays.

These displays are particularly visible on a lawn, where two males may posture at each other for periods of ten or twenty minutes at a time. Often they never come to within a meter of each other but, just occasionally, physical warfare breaks out. Later in the season, when the adjacent males are both paired, such posturing (and even fights) may have extra protagonists-three or even four territories may meet on a lawn and the females may join in.

A Long Breeding Season

It often seems as if the blackbird breeding season extends from early April through to the end of May. This Is indeed the time when they are at their most conspicuous, but many pairs already have a nest with eggs in the middle of March (or even earlier), and may continue with breeding attempts right through to July or even early August, provided the weather is suitable.

Early broods are often quite successful for the predators, such as cats, jays, magpies, and crows, which take such a toll on nests, are not yet active. During April, when most species have started to nest, the blackbird’s success is at its lowest (although clutch size is then at its highest); success is higher in May and June when there is plenty of covers for the birds to nest in.

The clutch of three to five (sometimes six) eggs is laid in a nest which, although it contains a layer of mud, is lined with grasses. The blackbird’s eggs are a dull blue-green with reddish-brown speckling. Incubation, carried out mainly by the female bird, lasts for about a fortnight from the laying of the penultimate egg and the young are then fed-on worms and other animal food at increasingly frequent intervals by both parents for two weeks before they fledge.

This is their most vulnerable period for they are still unable to fly for up to 36 hours after fledging and are at the mercy of cats or any other predator able to withstand the brave and noisy attention of the parent birds. The youngsters may be fed by their parents for a further three weeks-first by both and then later only by the male, as the female already be sitting on her next clutch.

The Annual Moult

At the end of the breeding, season-which may be as early as mid-June in a dry year when the blackbirds are unable to find their food easily, or as late as mid-August in a wet summer- the adults undergo a complete molt to replace all their feathers. At the same time, the partial molt of the juveniles takes place and, for a few weeks, the blackbirds, although still present, are not at all easy to see.

However, a little later they become much more conspicuous, particularly to anyone with an orchard and windfall apples or with ornamental shrubs bearing a good crop of berries. Although worms are readily taken at all times of the year, most of their food during the autumn and winter is fruit (where bird-table food is not being exploited)

Urban Versus Country Populations

Our own breeding blackbirds are mostly fairly sedentary, although ringing has shown some movement, particularly from northern and upland areas in winter. Indeed, it is certain that the majority of blackbirds hatched in Britain move no more than a kilometer or two from their natal territory throughout the whole of their lives.

This has enabled detailed research to unravel the different pressures on different populations of blackbirds. In urban habitats it appears that adult blackbirds survive very well indeed – the food provided for them on bird tables keeps them it and healthy through even the coldest weather and the experience of their first few years of life teaches them, as it does most urban birds, to avoid cats and cars.

Their nests and eggs are, however, much more likely to be preyed upon or fail for other reasons, and the few young that they raise have a difficult time surviving all the hazards of city life. In the country, on the other hand, more young are produced by each breeding pair and they are able to survive better-which is just as well, for the overall adult mortality is higher in the country than it is in urban areas.

This seems to be due largely to shortages of food during the winter-urban birds, which have access to more food, put on a greater amount of fat in hard weather to keep them going. Since they are easy to observe, blackbirds are among the best species to keep notes on. For instance, if the birds in your garden are territorial, or possess distinguishing features. It is possible to list the feeding preferences of particular individuals.

Communal Roosts

Well during the winter, in particular, blackbirds spend their nights together in communal roosts. These are often at traditional sites and it has been shown that they choose areas that offer them shelter and safety from predators. The shelter enables them to conserve heat most efficiently, and gathering together in one roost may even serve the birds as an information exchange so that those with sub-standard feeding sites are able to follow out those who know of the best feeding areas.

These roosting birds are not just the home-grown British population, for vast numbers of blackbirds from Germany, Denmark, Nor- way, Sweden, Poland, and Finland come to Britain for the winter. Many British birds stay in their own home territories but, although some remain territorial, many tolerate visits from foreign migrants. In the spring, when our own birds are just starting to breed and have already acquired their bright orange beaks, many of the migrants still sport their dull brown winter beak color.

Albino Blackbird’s

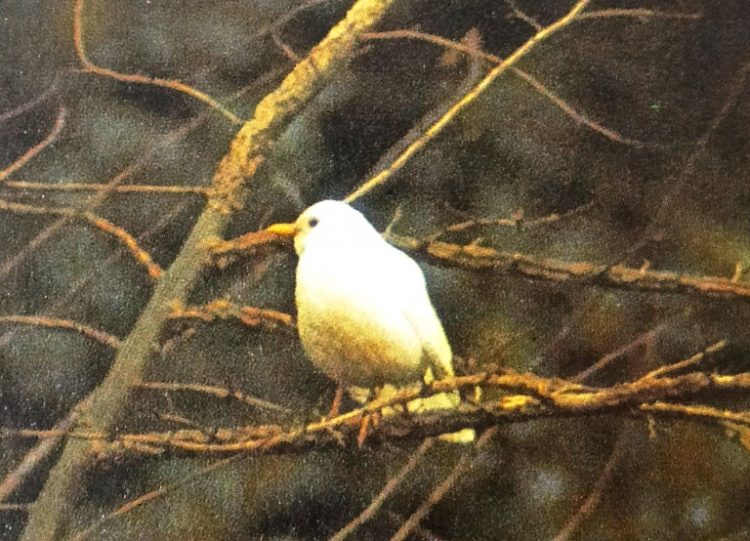

One feature of the black-bird species is that it is prone to albinism. There have been many records of pure white male blackbirds which still show the orange (or yellow) beak and eye ring (and, in the albino, legs). Often the birds just show a few white feathers flecking the plumage, but this is sometimes neatly symmetrical and progressive – becoming more and more apparent year E after year.

The whiteness does not seem to put the birds at such a disadvantage that they get caught by cats or other predators, however. In some areas, albinism is transmitted genetically within the population, and pockets of partially albino birds persist for several years.

Above: A male blackbird with jet-black plumage and a bright orange bill. This bird is easily recognizable by its jaunty, hopping gait and also by its habit of standing with head cocked to one side, listening for worms underground. The melodious, fluting song of the blackbird the one heard most often in our dawn choruses-is also easily identifiable. The blackbird has a danger note as well – a harsh, persistent ‘pink-pink-pink-pink’ call.

Blackbird (Turdus merula) Resident in town and country gardens, hedgerows, and woodland edges throughout the British Isles 25cm (10in).

An albino blackbird – This species seems to be prone to albinism, as many records show. The birds may be partially albino, with just a few white feathers here and there, or pure white, as here.

A female blackbird sunbathing, with wings spread wide. Note the speckling on the breast. Blackbirds are one of the most common bird species in British gardens, on par with the robin and the acrobatic blue tit.

A juvenile blackbird – the body feathers of the young birds often have rich brown centers.

A blackbird’s nest (close to the ground) and the eggs unlike the nest of the song thrush (a close relative of the blackbird), which is just made of bare mud, this nest is lined with grasses. A clutch of three to five eggs is usual.

A young blackbird in first-year plumage with brown primary feathers.

Also Read: Two-Tailed Ancient Bird Discovered / The Mystery Bird “Yellow-Billed Oxpecker