Dighton Rock was discovered in the former town of Dighton.

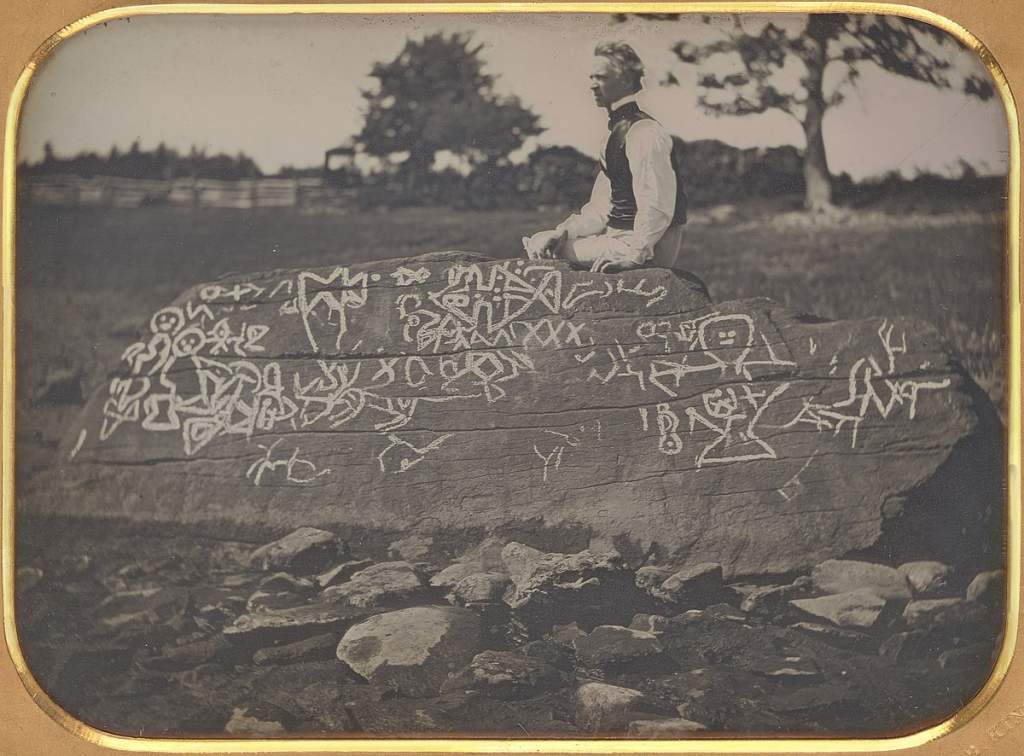

A small museum located in Berkley, Massachusetts, on the shores of the Taunton River, holding a single but massive exhibit. Installed here in 1963, this rock weight 40 tons and was fished from the riverbed, a mysterious, tide-washed boulder. The rock carved with indecipherable inscriptions has intrigued scholars since the 17th century because of its indecipherability.

In addition to the crude drawings of people along with known writing, the petroglyphs are primarily composed of straight lines with geometric shapes. People are convinced that the doodles represent a secret message, even though they seem like random doodles made by bored people. About 5 feet high, 9.5 feet wide, and 11 feet long, the Dighton Rock stands approximately 5 feet from the ground.

Inscriptions are on an inclined surface that was once visible from the sea by approaching boats and ships. There was, speculation throughout the centuries that the carvings were left by visitors to the coast in order to catch the attention of subsequent maritime explorers passing through.

Dighton Rock appears in the British Museum as a drawing made by Rev. John Danforth in 1680, which contains petroglyphs. There is, however, a conflict between Danforth’s drawing and other reports made at the same time about the rock. According to Cotton Mather’s book, The Wonderful Works of God Commemorated, the rock is described as follows:

One of the other Curiosities of New England is the mighty Rock, which is surrounded by a river on the perpendicular side, and part of it is covered at High Tide. Half a score lines of deep engraving are found on this rock, about ten feet long, and a foot and a half wide, filled with strange characters: which suggests odd thoughts about them that were here before us, as there are odd shapes in that elaborate monument.

In the 19th century, the rock was mentioned by many public figures and popular publications. It should be mentioned in presidential candidate letters to newspapers, according to poet and critic James Russell Lowell: “If letters need to be written, we might take advantage of the hieroglyphics on the Dighton rock or the cuneiform script, which are capable of yielding new meanings to each new interpreter.” Lowell may have contributed to popularizing the rock by making other references to it in his widely circulated satirical writing.

Theories of different types

An influential theory was put forward by a Danish scholar named Carl Christian RaIn in 1837, which proposed that the carvings were created by Vikings and represented Thorfinn Karlselne’s journey to the North American coast, where his wife Gudrida gave birth to his son Snorro, in the Norse saga. In response to Raln’s theory, the Rhode Island Historical Society contacted their Danish friends, who together provided ample evidence for Hop being located near the Taunton River.

The theory that the Vikings explored North America pre-Columbianly was almost universally accepted from 1837 onwards as a result of Rafn’s research. There was a long chain of evidence leading up to Dighton Rock. Delabarre of Brown University, the late professor who discredited the Viking theory of the rock, shredded the theory in 1916. Rafn’s book reproduced doctored copies of the drawings of the society, which Delabarre found to be grossly incongruous with the society’s actual drawings. As a result of Rafn’s additions to the drawings, his theory appears to have been supported by many lines.

Aside from the lines and markings on the inscription, Delabarre noticed a name and the date 1511 written across. It can be translated to “I, Miguel Cortereal, 1511″ with the help of Delebarre’s version of the message. I became a chief of the Indians here by the will of God.”

How did Miguel Cortereal come to be known as Miguel Cortereal? His brother Gaspar had gotten lost two years earlier near Newfoundland and Miguel Cortereal set off from Lisbon two years earlier in search of him. When the three ships reached the place where Gaspar’s party landed, they departed in different directions to search for further information.

A rendezvous with Miguel was not held up as a result of the ship carrying Miguel failing to appear. It is unknown whether Miguel and the ship made the return trip to Portugal, while the other two ships did. In 1502, Miguel Cortereal reached Mount Hope Bay and sent men ashore near Dighton Rock, Delabarre speculated.

Possibly Miguel joined the Wampanoag tribe after he had fought the Wampanoags, or maybe he was shipwrecked, or maybe another number of years were spent watching over vessels along the coast with the Wampanoags by Cortereal. In 1511, after hopes of rescue had dimmed, he carved his message into the rock, so that future generations would be able to see it.

A great deal of support exists for Delabarre’s theory among Portuguese people, but not much else. Known as The Northern Voyages, it is a book written by American historian Samuel Eliot Morison in 1971 that has been pretty harshly criticized. It was installed in a museum in a nearby park, Dighton Rock State Park.

A record of its historical significance has been placed on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) since 1971. Gavin Menzies, the author of the book American Adventure, suggests that these carvings may actually be Phoenician and Chinese.

Dighton Rock State Park, established in 1955, does not attract many tourists because of the endless debate between scholars about the rock. It was the only tourists visiting the museum when Roadside America visited.

He and a colleague, Bob, both said they didn’t see too many people at the park. Milt told them, “It’s not visited often.”. A picnic area and parking facilities have been built in the area around Dighton Rock. Another rock, Profile Rock, made of 50,000 slate pieces, shares space with the replica of the real rock (about five miles away).

Related Reading: Newspaper Rock, Covered with Hundreds of Ancient Indian Petroglyphs