The Epic Tale of Francisco Vázquez de Coronado. There was an extraordinary series of encounters between Spanish explorers and native North Americans during the late 1530s and early 1540s. The path Hernando de Soto cuts through parts of ten future states in the Southeast is a path of death and destruction. Over a thousand miles along the Pacific coast of the Americas were sailed and charted by Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo.

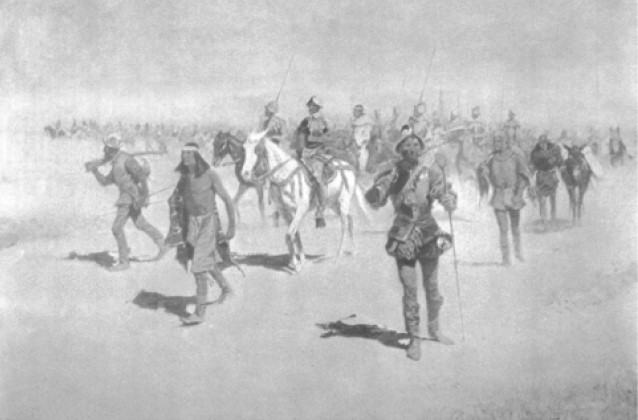

There was also an expedition led by Francisco Vázquez de Coronado in the Southwest from 1540 to 1542, which went from the northern part of New Spain into the present-day territories of Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma, and Kansas. Coronado was born in 1510 in Salamanca, Spain. He was the son of a wealthy merchant.

His chances for advancement at home were slim since he was the second of four sons, and the family estate had already been promised to his older brother, so he had no chance of advancing at home. After being taken into the retinue of Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza in 1535, he moved to Mexico to continue his military career.

As a result of his relationship with the viceroy, Coronado was appointed governor of Nueva Galicia, which included parts of the modern Mexican states of Sinaloa and Nayarit as well as most of Jalisco. In 1538, led by the Franciscan Father Marcos de Niza, Mendoza and Coronado led a small exploring party, including Cabeza de Vaca’s famous slave Esteban, into the unknown territory of the north, inspired by the incredible journey of Cabeza de Vaca. As Esteban was killed at Cbola, a Zuni town, Marcos returned to tell a wonderful story comparing New Mexico’s material wealth with that of Mexico and Peru’s. Probably, Fray Marcos never actually visited Cbola for fear that he would meet the same fate as Esteban.