Mohawks are Native American groups, part of the Five (later Six) Nations of the Iroquois, or Iroquois Confederation, whose territory included much of upstate New York. The Mohawks, along with the Senecas, comprised one of the two main fighting wings of the Iroquois Confederation during the colonial period.

They participated in wars against the French and their Algonquin allies and served as the principal enforcers of British-Iroquois policy following the creation of the Covenant Chain alliance in the late 1600s. The Mohawks, or Ganienkeh (people of the place of the flint), occupied the Mohawk River region west of Albany in present-day New York.

They guarded the “eastern door” of the Iroquois Confederation, where they became the first Iroquois to encounter European trade goods, which they acquired during raids against their Algonquian neighbors to the north. Soon they discovered Europeans as well. In July 1609, allied Algonquins from the St. Lawrence River Valley defeated some 200 Mohawks near the southern tip of Lake Champlain.

The Algonquins brought along a handful of French soldiers, including Samuel de Champlain, whose firearms helped carry the day. The following year, the Algonquins and French defeated the Mohawks in an even larger battle. Saddled with technological inferiority, the Mohawks, demonstrating the independence of action that characterized membership in the confederation, sought and obtained a trade alliance with the Dutch at Fort Orange (Albany).

This agreement brought them the firearms they desired. Armed and aggressive, the Mohawks interjected themselves into the fur trade during the mid-17th century. Handicapped by their limited access to valuable furs and European trade centers, Mohawks initiated a series of systematic wars, known as the “Beaver Wars”, to secure direct access to both fur supplies and European traders.

Their main targets were the Mahicans, who managed trade with the Dutch at Fort Orange. They also targeted the Hurons, whose 494 Mohawks controlled western fur resources and blocked Mohawk access to fur supplies in the St. Lawrence Valley and the Great Lakes region. In the 1620s, the Mohawks drove the Mahicans to the east of Fort Orange.

They then took control of the fur trade with the Dutch. The conflict between the Mohawks and the Mahicans continued intermittently for the next fifty years until English authorities brokered a peace deal in 1673. That arrangement formally brought the Mahicans under Iroquois control. The Hurons fared no better. In the 1640s, the Mohawks and the Senecas invaded Huron territory and, over the next decade, burned Huron towns and villages.

They also destroyed their agricultural fields, systematically exterminated entire groups of Hurons, and forcibly assimilated most of the survivors into Iroquois society. By 1653, the Hurons had been eliminated as an independent political entity. When the English supplanted the Dutch as the colonial masters of New York, the Mohawks effortlessly shifted their trade interests to the newcomers.

They became so invested in their new friendship with the English that Mohawk leaders refused to ratify a peace agreement between the Iroquois Confederation and the French. As a result, in 1666, the French twice sent punitive expeditions into Mohawk territory, finally forcing the Mohawks into submission.

Yet the evolving Iroquois-English alliance, known as the Covenant Chain, afforded the Mohawks a means to cast off French influence. As the Iroquois Nation closest to Albany, the Mohawks cultivated an especially close relationship with English traders and officials. The Iroquoian wars of the late 17th century gradually merged with the European wars between the French and the British.

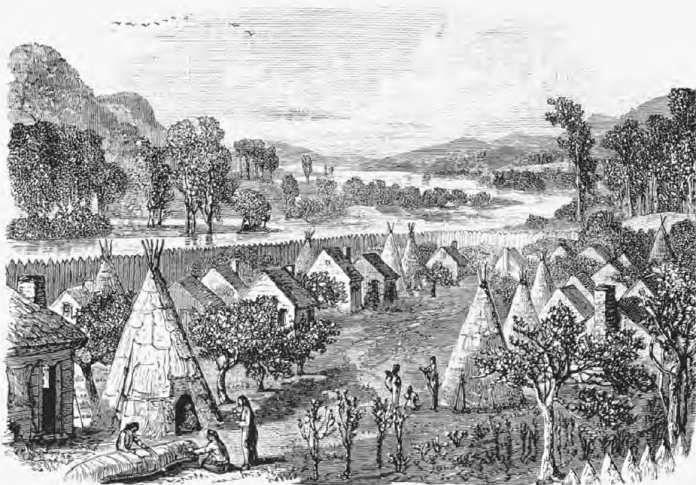

And the Mohawks, more than any other Iroquoian people, supported the English against the French. The results, however, did not always favor the Mohawks. During King William’s War (1689–1697), the Mohawks suffered heavily at the hands of the French and their native allies. In 1693, in particular, the French destroyed three large Mohawk villages and French-allied warriors took over 300 Mohawks into captivity.

The rest of the Five Nations Iroquois suffered similar defeats until, at last, the Iroquois Confederation concluded a peace treaty with the French in 1701. In it, they pledged to remain neutral in future disputes between France and England. Maintaining that neutrality proved difficult for the Mohawks because of their close proximity to the British, whose commerce and culture steadily seeped into Mohawk society.

Protestant missionaries were particularly active, winning converts among Mohawk leaders and commoners alike. Not surprisingly, during both Queen Anne’s War (1702–1713) and King George’s War (1744–1748), Mohawk warriors fought to aid the British cause.

Then, during the French and Indian War (1754–1763), Mohawk military aid to the British intensified even further. This was in no small part due to the influence of Sir William Johnson, the British superintendent of Indian Affairs for the northern colonies, who maintained a residence among the Mohawks and twice married Mohawk women.

Mohawk war parties helped Johnson achieve victory at the Battle of Lake George (1755) and played an important role in the successful campaign against Fort Niagara in 1759. The Mohawks’ close relationships with the British perhaps afforded them greater status than other members of the Iroquois Confederation during the 18th century, but ultimately it proved their undoing.

During the American Revolutionary War, the Mohawks refused to abandon their attachment to the British, a stance that helped to transform the struggle for American independence into an Iroquoian civil war that brought about the end of the confederation.

Read More: Esopus Wars – Conflict between European Settlers and Natives in North America