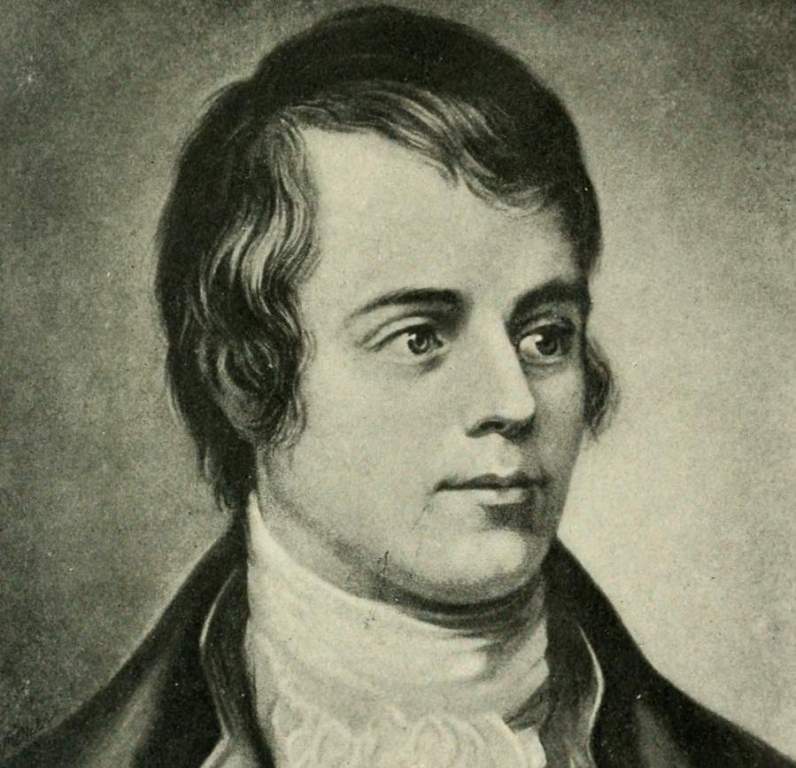

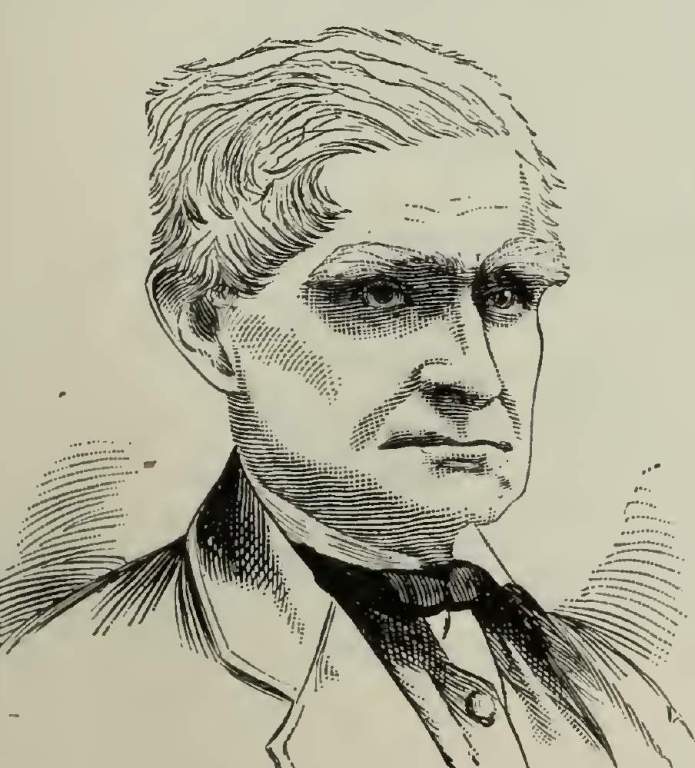

Thomas Carlyle was a famous Scottish critic, philosopher, and historian. He was born at Ecclefechan, Dumfriesshire, on 4 December 1795. A leading Victorian writer, he profoundly influenced art, literature, and philosophy during the 19th century. He was the eldest son of James Carlyle, a Mason and farmer. James Carlyle was a serious God-fearing man of tremendous intellectual power, while his wife, Margaret Aitken, is represented as affectionate, pious, and intelligent.

The elder Carlyle was a member of the Relief Church. He intended his son Thomas to become a minister in this church. With this object, he was carefully educated at the parish school and at the burgh school of Annan. In his fifteenth year, he was sent to the University of Edinburgh. He studied under professors such as Leslie, Playfair, and Dr. Thomas Brown. Here he developed a strong taste for mathematics, a subject in which he achieved significant proficiency.

Having renounced the idea of becoming a minister, after finishing his curriculum in 1814, he became a teacher for about four years, first at Annan, then at Kirkcaldy, where he conducted the burgh school, and left behind him the character of an over-stern disciplinarian. At the latter place the celebrated Edward Irving, whom he had first met during his school-boy days at Annan, was then also acting as a teacher, and the two became intimate friends.

In 1818 he moved to Edinburgh, where he supported himself with literary work. He devoted much time to German study and studied through a varied and extensive course of reading in history, poetry, romance, and other fields. His first literary productions were short biographies and other articles for Edinburgh, an extensive work edited by Brewster.

After three years of arduous work and poverty in Edinburgh, his health broke down, and he retired to his father’s farm in Dumfriesshire. He was then engaged to tutor Mr. Buller’s sons, one of whom became well-known in public life. This post he held for two years. During this period his career as an author may be said to have really begun, with the publication of his (Life of Schiller) in London (Magazine) in 1823. Therefore, this work was enlarged and published separately in 1825.

In 1824 he published a translation of Legendre’s Geometry, with an essay on proportion, by himself, prefixed, which Prof. De Morgan characterized as thoughtful and ingenious, as effective a substitute for Euclid’s fifth book as could have been given in space. During the same year, he translated Goethe’s Apprenticeship (Wilhelm Meister). This work, which like the others and admired, mentioned was anonymous, was favorably received. However, some critics objected to the translator’s enthusiastic fondness for German idioms. During his tutorship, he spent some time in London, where Irving lived at the time. He was next engaged in the translation of German romance novels published in 1827.

In 1826 he married Miss Jane Welsh, daughter of a doctor at Haddington, and a lineal descendant of John Knox. After his marriage, he resided in Edinburgh and then moved to a farm in Dumfriesshire belonging to his wife. This farm is about 15 miles from Dumfries. This place, Craigenputtock, he describes in a letter to Goethe. Moreover, in 1828, as the loneliest nook in Britain, an oasis in a wilderness of health and rock, among the granite hills and the black morasses that stretch westward through Galloway almost to the Irish Sea.

Here he wrote a number of critical and biographical articles for various periodicals, such as the “Edinburgh Review” the “Foreign Quarterly”, and “Fraser’s Magazine”; and here was written “Sartor Resartus”, the most original of his works, the one which first brought him fame, and which has had perhaps a greater influence on the minds of readers than any single work that could be named.

The writing of “Sartor Resartus” took place over several years. It seems to have been finished in 1831, but the publishers were shy about it. As a result, it was not released to the public until 1833-34, through Eraser’s Magazine. The whimsical title of this work literally “The Tailor Repatched” is a translation of an old Scottish song (The Tailor Done Over).

The book professes to be an exposition for English readers of a new philosophy, the philosophy of clothes, first thought out and expounded by Diogenes Teufelsdrockh (Devil’s Dirt, Asafoetida), professor of things in general in the German university town of Weissnichtwo (Know-not-where, Scotch Kennaquhair); with biographical particulars regarding the professor, and miscellaneous thoughts, reflections, and speculations of his not strictly connected with his philosophy.

The professor is in fact Carlyle himself, and the work is autobiographical. It is inspired by a distinctly didactic purpose, preaching through its wonderful intermixture of the humorous, the grotesque, the sublime, the pathetic, the solemn, the profound, welded together by a poetic or even a prophetic spirit, the doctrines of truthfulness, obedience, duty, work, and, above all, hatred of sham.

The publication of “Sartor” to which no author’s name was originally attached soon made Thomas Carlyle famous, and on his removal to London early in 1834 he became a prominent member of a brilliant literary circle embracing John Stuart Mill, Leigh Hunt, John Sterling, Julius Charles, Augustus William Hare, Maurice, and his old pupil Charles Buller. He fixed his abode at Cheyne Row, Chelsea, where he spent most of his time from then on. His next work was on the French Revolution, published in 1837.

This, though a work of immense research, is hardly a history in the ordinary sense of the term. It is rather a series of powerful pictures, in which we see the most significant events and are intimately acquainted with the chief actors of that stormy period. Of it, the “Westminster Review” remarked, “No work of utter genius, either historical or poetical, has been produced in this country for many years”.

The first volume of the “French Revolution” while still only in MS., was unfortunately burned in John S. Mill’s possession. The author immediately worked and wrote it again. About this time, and in one or two subsequent years, he delivered several series of lectures, the most important (On Heroes and Hero-worship) being compiled in 1840. Chartism, published in 1839, and (Past and Present), published in 1843, were small works bearing more or less on current affairs.

In 1845 appeared Oliver Cromwell’s Letters and Speeches, with Elucidations. This was a work of extensive research, and brilliantly successful in indicating the character of the mighty Protector. In 1850 came out his Latter-day Pamphlets / a series of tracts dealing with political subjects, and assailing with extraordinary vehemence, not to say virulence, the most prominent institutions and characteristics of modern England and its people. As a result of its exaggerated language and support for harsh and coercive policies, these works were very repulsive to many people. He also wrote the life of his friend John Sterling, published in 1851, and regarded as a finished and artistic performance.

The largest and most laborious work of his life, “The History of Friedrich II of Prussia”, called Frederick the Great, came out in three volumes, the first two volumes in 1858, the second two in 1862, and the last two in 1865, and after this time little came from his pen. His choice of Frederick as a hero strikes most people as remarkable, a feeling that the writer himself wasn’t prepared for. According to him, he selected him for historical treatment because he was the author of almost the only meaningful and substantial work of his time.

That there was nothing of the hypocrite or sham about him; and that “How this man, officially a king withal, comported himself in the eighteenth century, and managed not to be a liar and charlatan as his century was, deserves to be seen a little by men and kings, and may silently have didactic meanings in it”.

He is reported to have said in conversation that he had tried to put some humanity into Frederick but found it challenging work. Of the immense labor and research shown in this work, of the descriptive and narrative power displayed on almost every page, of the vividness with which a portrait is drawn, or an event put before us, it is almost impossible to speak too highly. At the same time, it cannot be denied that too often the author’s powers as a skilled advocate have been enlisted in favor of “Vater Fritz” and his doings. Frederick the Great was translated into German and is popular in Germany.

In 1866, having been elected Lord Rector of Edinburgh University, he delivered an installation address to students “On the Choice of Books”. While still in Scotland the sad news reached him that his wife had died suddenly in London. This was a severe blow to Carlyle. Because Mrs. Carlyle, besides being a woman of exceptional intellect, was a most devoted and affectionate wife. On her tombstone beside the Haddington abbey church, he recorded her virtues and his sorrow for her loss. He also stated that at her death his light was gone out.

From this time his productions were mostly articles or letters on topics of the day, including “Shooting Niagara”; and “After?” in which he vented his serious misgivings about the Reform Bill of 1867. An unimportant historical sketch, “The Early Kings of Norway” appeared in 1874, but was written long before.

Thomas Carlyle died at Chelsea and was buried at Ecclefechan. He left the Craigenputtock estate to the University of Edinburgh. He settled that the income from it should form ten bursaries to be annually competed for—five for mathematics proficiency and five for classics (including English). In 1881 Thomas Carlyle’s reminiscences of his life were published by J. A. Froude, who also published a biography of Carlyle (1882-84), and edited “Letters and Memorials of Mrs. Carlyle in 1883”. In the following year, the Correspondence of Carlyle and Emerson between 1834 and 1872.

Thomas Carlyle command of the English language was greater than that of almost any other prose writer, and his style was unique. It has been called unnatural, a distortion of the English language, a mere literary device or affectation to attract attention, but this is only a superficial criticism. There may be a tendency to be eccentric, uncouth, rugged, and extravagant, but one who understands it has to realize that it was simply the natural way of his thoughts being expressed.

It grew and developed as the writer grew and developed, and in his hands was an instrument of unsurpassable power. Lowell has said of him, “Though not the safest of guides in politics or practical philosophy, his value as an inspirer and awakener cannot be overestimated.” It is a power that belongs only to the highest order of minds, for it is none other than divine fire that can so kindle and irradiate.

The debt due him from those who listened to the teachings of his prime for revealing to them what sublime reserves of power even the humblest may find in manliness, sincerity, and self-reliance, can be paid with nothing short of reverential gratitude. Thomas Carlyle died in Chelsea, London on 5 Feb. 1881. Thomas Carlyle Studies scholarship has enhanced his standing since the 1950s, and he is now considered “a monument to our literature who simply cannot be spared.”

Read More – Biography of Andrew Ryan McGill