Achilles Pugh was born in Chester County, Pa., on March 10, 1805. Four years later, his father (Thomas and Esther (Gatchell) Pugh) settled in Cadiz, O. By the age of 17, Achilles Pugh entered the Cadiz Informant office to learn the printers’ trade. Achilles Pugh founded A.H. Pugh Printing Company in Cincinnati, a publishing firm.

In 1827, Achilles Pugh moved to Philadelphia to perfect his business skills. In 1830, he found employment in Cincinnati and soon became manager of the Evangelist periodical. In 1832, he married Miss Anna Maria Davis, daughter of John Davis, of Bedford County, Va. A few years later, he formed a partnership in a contract printing business with Morgan & Sanxay.

It was then that trouble overtook him. The Ohio Anti-Slavery Society was organized in April 1835. An executive committee led the organization, which also published a newspaper, “The Philanthropist”, in Clermont County. After printing a few copies, they asked him to take the press, type, and publish the paper in Cincinnati.

His partners refused, the connection was dissolved, and he contracted to publish it alone. Unable to hire a building for the purpose owing to the obloquy attached to the cause, he erected one at the rear of his residence on Walnut Street, between Sixth and Seventh Streets. He did printing as a matter of business. “If,” reasoned he, “slavery cannot stand discussion, then slavery is wrong; therefore, as a printer, it is in my business to print this paper, charging only the ordinary rates for the work.”

As soon as the newspaper was published, it was evident from the attitude of the city press that a storm was brewing. This storm broke at midnight on the 12th of July. In 1836, a band of men broke into his office, frightened into silence by a boy sleeping there. They destroyed the week’s issue and dismantled and carried away parts of the press. Not to be discouraged, Mr. Pugh had his own press purchased and was at work at 11 o’clock the next day printing his weekly issue.

A few days after removing his press from his office, he moved to the corner of Seventh and Main Streets. At sundown on the night of the 29th, a second mob assembled, broke into his office, pitched the type cases and press into the middle of the street, and were about to set it on fire when his honor, the Mayor, Samuel W. Davies, mounted the pile and addressed the mob.

He complimented them for having done so well thus far but advised against the conflagrating process, as it would endanger the adjacent property. Thereupon, they hauled the press by rope and, with much noise and shouting, cast it into the Ohio River. After the second attack, he printed the paper at Springboro, in Warren County, and brought down “the abominable sheet” by canal to the city.

In the exciting era, he was a marked man and very much wanted as an object of adornment with tar and feathers, but by keeping in after dark, keeping out of certain parts of the city when it was light, and possessing a powerful muscular physique, he was blessed to escape being made a subject of ‘high art.’ ’Scowls and cold shoulders were given to him in abundance.

These he bore with equanimity, and, as the cause of anti-slavery gradually advanced, many a dollar was privately slipped into his hand, which helped the flight of colored fugitives by the underground railroad. Even southern traders provided some of the money. No questions were asked, only for the money. The recipients seemed strangely indifferent as to its application. As they gave, they laughed and looked queer. Until 1875, Mr. Pugh was closely associated with Cincinnati’s printing industry.

In 1837, he formed a partnership with Mr. Dodd and began the publication of the Weekly Chronicle with E. D. Mansfield and Benjamin Drake as editors. This paper was subsequently converted into a daily and continued until 1846, with Achilles Pugh as printer. Just as the paper commenced to make financial returns at the expense of its establishment, at the instigation of his church and his own desire to avoid evil, every advertisement regarding the sale of spirituous liquors was taken out of the paper, and with them nearly all the business profits. Thus, he was always ready to sacrifice worldly gain for righteousness.

He and John Butler were chosen for the Orthodox Friends’ Commission Executive Committee in 1869. This was in connection with the duties assumed under President Grant’s invitation to examine the Indian agencies of the Central Super-intendency. During a ride in an unarmed buggy through Indian country, accompanied only by an ambulance driver and guide, two wild Indians of the plains, Kiowas, overtook them, riding up on each side of them with their bows strung and their arrows in their hands, evidently designed to cause mischief.

Achilles Pugh used a strategy to get rid of them. Placing his hands in his mouth, he drew a complete set of false teeth and thrust them towards the nearest savage. He dropped his heavy, beetling brows in a ferocious scowl. His mouth was without support, and the chin and nose were positioned close. The Indians were horrified at the act and, putting spurs on their horses, disappeared in a flash. From very early life, he was a member of the Religious Society of Friends and was actively and devotedly engaged in church and Sabbath-school interests, as well as his own, but his broad Christian character and loving heart made him particularly unsectarian.

He was a life member of the American Bible Society and was constantly and unselfishly interested in the dissemination of Bible truth. The poor and unfortunate found in him a most generous friend, and he was so genial and well-informed that his company was a pleasure and an instruction. Though he suffered before his death, he was not confined to bed. He joined his family in worship, asking that the 14th chapter of John be read. We trust he is with the Savior whom he loved to hear.

The sketch of Achilles Pugh is from a lady friend. His family home was in Waynesville, and his place of business was in Cincinnati. I knew him for many years and greatly valued him for his sound sense, integrity, and social spirit. I believe he was married into Quakerdom and not born into it. Friends would never christen a son “Achilles.”

He once told me that one can’t understand the trying position of antislavery activists. To walk the streets and feel as you passed along that you were hated by many in the throngs you met, looked upon as a sort of moral firebrand sowing dissension between the North and South, was not a comfortable position for any man, and the natural effect upon the recipient was to engender a bitter, defiant spirit.

To live under the ban of public opinion, even for a righteous cause, requires a strength of moral heroism rarely possessed, so it withers spirits. King David wrote, “In my haste, I said all men are liars.” He might have said with equal pungency and been in no special hurry about the saying, “All men are moral cowards.” Achilles Pugh was a high-spirited, sensitive gentleman who would not submit to wrong. The newspaper of an association of printers harshly attacked him for his office conduct on one occasion.

He brought suit for libel and was awarded $500 in damages. On being asked why he did not call for the money, he replied, “I don’t want their money.” My object was to establish a principle. ” This, by indirect association, reminded me of an anecdote about John Van Buren, son of Martin Van Buren. They called him “Prince John.” He was a brilliant, waggish young lawyer with no great moral purpose. When his father was nominated for president in 1848, he took the stump in advocacy of the “old gentleman’s” cause.

The prince told the people he had now gotten hold of a moral principle—free soil; it was the first time in his life he had gotten hold of such a thing. To him, it was a novel sensation, quite refreshing, and he applied that moral principle to its fullest extent. In the sketch, Mr. Pugh is told how he scared two wild Indians of the plains who threatened his life by taking out his false teeth. He moved them in both hands slowly toward them, scowling ferociously. In telling me of the incident, he said, “As soon as I did that, they spurred up their ponies and were out of sight in a twinkling.

I suppose they thought the next thing to happen was that I would take off my head and throw it at them.” How did you think of it?’ I inquired. “I felt that something had to be done immediately. We were in serious peril, unarmed, and totally defenseless, and from experience, it flashed upon me to try my false teeth. The three Friends commissioners were preparing to retire for the night in a tepee in an Indian village. The place was crowded with squawks, and their children were gazing in wonder when one of us took out his teeth to clean. The whole crowd grunted, ‘Ugh! Ugh!’ and rushed out panic-stricken.”

It is the unknown that especially frightens savages, which has a further illustration in an anecdote told of a party of English circus men in Asia Minor, who, discerning a body of wild Arabs riding down upon them with hostile intent, their long spears at charge, commenced turning summersaults from the backs of their horses, and then looking at them from under and between their legs, when the Arabs turned and fled.

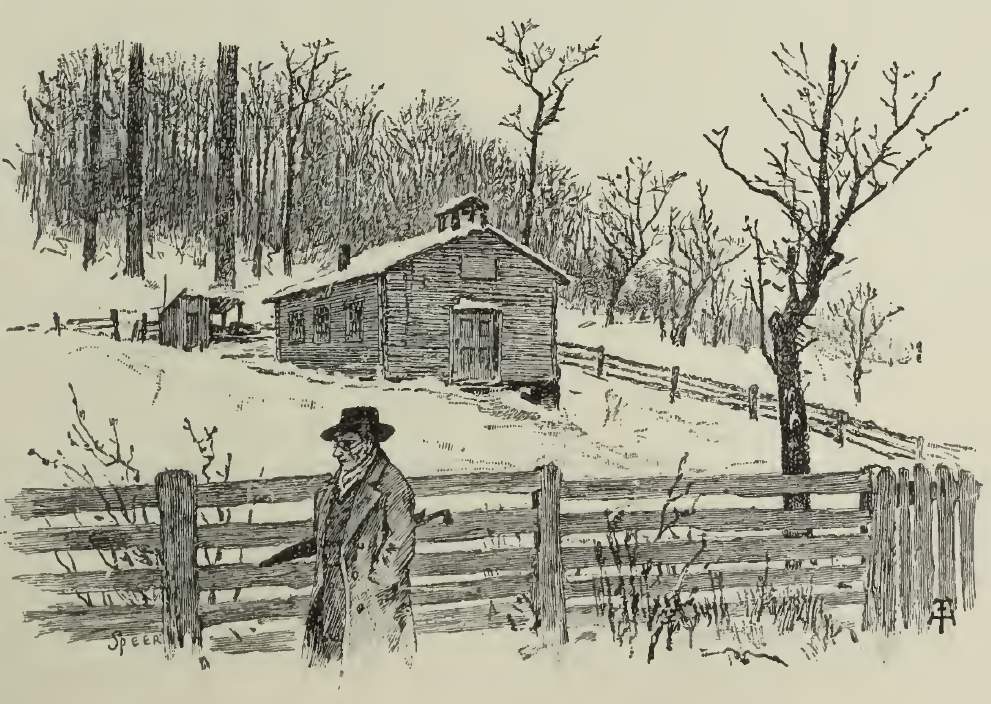

About three miles southwest of Waynesville, near the Little Miami, stood, on April 29, 1836, a small log house. On that day, joy was under its roof, for a boy was born in this small log house. The father was a Quaker and an abolitionist; he had begun as a surveyor, then a teacher, and finally a farmer. This newcomer was growing, and finally, when the Quaker father passed away, he thus wrote of him as

“His eye in pity’s tears” he would often saintly swim; he did to others as he would that they should do to him; “At rural toils, he strove; in beauty, joy he sought. His solace was in children’s words. And wise men’s pondered thoughts.”