Page Contents

It is difficult to identify the difference between a Tree Sparrow and House Sparrow. The House Sparrow is a species closely associated with man, sharing his environment and sometimes even becoming a pest. Another less numerous species the tree sparrow leads a relatively hidden life in woods and orchards.

The house sparrow is always seen in close association with man, his buildings, and his livestock. It might be possible to describe such an association as ‘commensal’, except that this would imply some form of mutual benefit or at least no detriment to either partner in the association. Short of enjoying its presence, we derive little benefit from the house sparrow.

The bird, on the other hand, while gaining access to plenty of good nest sites (at no cost to us), oversteps the bounds of commensalism in its attacks on our garden plants. This becomes more serious when it attacks our cereal crops: the sparrow ceases to be commensal and becomes a competitor or, in plain terms, an agricultural pest.

House sparrows are not normally birds of open environments such as hillsides or moors. In the vicinity of farm buildings, however, especially those with livestock, a colony of house sparrows is likely to be present. The birds are also common bird-table visitors, eating almost everything that is put out for them. They even feed on scraps of meat, if it is ever available to them.

Variations in Plumage

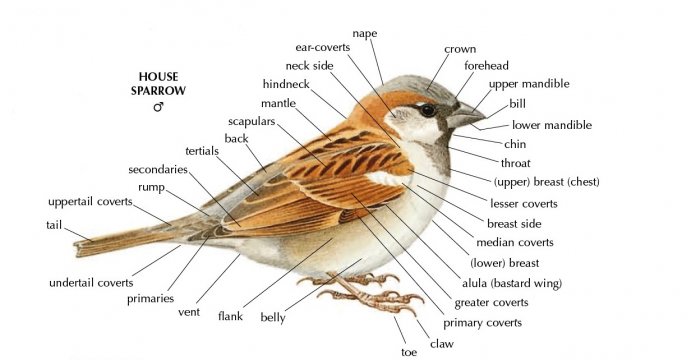

In spring, the male house sparrow is an attractive bird, with a gray crown bordered by rich chestnut brown. His back is a mixture of rich browns fringed with golden buff, his breast is grayish fawn and beneath the chin is a fan-shaped black bib. In winter, he is drabber since many of his body feathers have broad buff fringes which gradually wear away to expose the colors beneath in early spring.

The upper plumage of the female (both in summer and winter) is a mixture of sandy or grayish fawns and pale browns, and she is grayish beneath. Until they moult in their first autumn, young birds of both sexes resemble the females. If you travel about in Britain and Ireland, you may notice that house sparrows living far from towns have much brighter plumage than those living in the industrial conurbations, where the sparrows seem particularly dark.

In such circumstances, some species of animals have adapted by changing color to improve their camouflage. Best known is the peppered moth, normally white with a black peppering of spots. By the process of natural selection, this moth has gradually evolved darker and darker colors, which improve its camouflage on the grimy trunks of city trees. There was some debate whether house sparrows, too, were exhibiting this change (which is called ‘industrial melanism).

Experts examined the sparrows of the various shades and a strong superficial correlation was indeed found between darker plumage and more industrialized areas. Washing the feathers of all color types with a strong detergent, however, revealed that the darker ones had been contaminated with soot and other industrial grime, and thus their somber shades were only ‘skin deep.’

Feeding Habits

The house sparrow is an opportunist feeder, taking what food is easily available in the greatest abundance at the time. The diet includes seeds, buds, leaves, shoots, flowers, and a vast variety of human food waste and leftovers. Our sparrows are representatives of the mostly African weaver-bird family, some members of which are as devastating to crops as plagues of locusts. It is not surprising, then, that our house sparrows flock to the corn at harvest time.

Although each bird eats only a few grams of grain in a day, the house sparrow has an extremely wide distribution, and flocks often contain hundreds of individual birds. The nationwide total of house sparrows is so high that the species is a serious pest, causing many millions of pounds worth of damage each year.

Many gardeners are incensed by house sparrow attacks on their flowering plants. We put our food for them, which they take greedily, only to start to tear apart the crocus and primula flowers when they appear. Although it may be of little comfort to the gardener, there is at least an explanation for this. Notice how frequently it is the yellow flowers are attacked.

Yellow coloration is associated with flowers that have a particularly strong attraction for pollinating insects, and tend to occur together with a rich supply of nectar. Yellow crocuses, for example, have far more nectar than purple ones. It is this nectar at the base of the flowers that the sparrows are seeking.

Formation of Flocks

Flocks are very much a part of sparrow life. They are an effective means of exploiting the local abundance of food (as in cereal fields) and offer considerable protection from predators. They start to form in late summer and are often composed largely of juvenile birds. These flocks roam over a distance of several miles.

In winter, they join with other species, particularly finches and buntings, on stubble or weedy ground, or around places where livestock are fed. From late summer onwards, roosting, too, is regularly communal. Sometimes the roosts are within buildings, and sometimes in the dense shelter provided by rhododendron, hawthorn, or blackthorn thickets, or ivy-clad trees or buildings.

Nesting Sparrows

House sparrows can be seen around their nest sites in almost any month of the year, though attendance is at its lowest in late summer and early autumn. Attendance remains low through the winter, increasing as days lengthen and the temperature rises. Most nests are under the caves of houses, or in some other cavity in a building. Some are in haystacks and more natural sites such as crevices in cliffs or in thorny or dense shrubs like hawthorn. Usually, several pairs build nests in a loose colony.

The song of a territorial male house sparrow is a monotonous, repetitive ‘chirrup’, a familiar noise-chosen site, often adopting a squat, fluffed-up posture. Just as familiar is the sight of the female, perched on the roof or guttering, wings drooped and shivering, soliciting the male’s attention?

Sometimes there is a communal display, which becomes more and more exciting, sometimes even out of hand, developing into a rough-and-tumble chase. Often a single female is the center of attraction for numerous males. All as he sits close to his Eggs are laid from March through to August, with each pair attempting two or three, sometimes four broods in a season.

Their colors vary from off-white to dull brown, and all are flecked with a rich brown. Four or five is the usual number, but clutch Sizes range from two to seven. Incubation takes about 12 days, but the time is more variable than in most birds. The young fly after 11 to 18 days, depending on weather conditions and food supply.

The Tree Sparrow

In many ways, the tree Sparrow can be considered as the house Sparrow’s country cousin’. It is a slightly smaller, more muscular-looking bird, about two-thirds the weight of its larger relative. The sexes are similar in plumage; the all-brown cap, the small black bib, and the characteristic black spot in the center of a white cheek distinguish them from the house sparrow. Their call, a rich, fruity chirrup, once heard and learned is an excellent way of separating the two species at a distance or in flight.

Tree sparrows are just as catholic in their food choice as house sparrows but tend to shun the presence of man, usually feeding and nesting at a distance from human habitation. The display pattern and the breeding season are closely similar to those of the house sparrow. The tree sparrow lays from two to eight eggs, often, about six densely flecked with gray-brown. The nest is regularly in a hole in a building or a tree. In the latter case, the hole may be a natural one, or else the disused nest of a woodpecker.

Tree sparrows readily occupy nest boxes, and are pugnacious in their tenancy of them, even evicting other birds such as blue or great tits, and building their own nests on top of those of the first occupiers. Incubation lasts 12 days, sometimes less, and the brood fledges after 10 days, or sometimes more. Tree sparrows are nowhere as numerous as house sparrows and have a much less widespread distribution in Ireland, northern and western Scotland, the Hebrides, and southwest England. So, we hope now, that you will understand the Difference Between a Tree Sparrow and House Sparrow.

Read More – The Hefty Raptor Savanna Hawk

Product You May Interest

- Feel Emotional Freedom! Release Stress, Heal Your Heart, Master Your Mind

- 28-Day Keto Challenge

- Get Your Customs Keto Diet Plan

- A fascinating approach to wipe out anxiety disorders and cure them in just weeks, to become Anxiety free, relaxed, and happy.

- Flavor Pairing Ritual Supercharges Women’s Metabolisms

- The best Keto Diet Program

- Boost Your Energy, Immune System, Sexual Function, Strength & Athletic Performance

- Find Luxury & Designer Goods, Handbags & Clothes at or Below Wholesale

- Unlock your Hip Flexors, which give you More Strength, Better Health, and All-Day Energy.

- Cat Spraying No More – How to Stop Your Cat from Peeing Outside the Litter Box – Permanently.

- Anti-aging nutritional unexplained weight gain, stubborn belly fat, and metabolic slowdown. Reach Your Desired Weight in a Week and Stay There.

- Get All Your Healthy Superfoods In One Drink