When did Merriam’s Teratorn become extinct?

Merriam’s Teratorn died out around 10,000 years ago.

Where did Merriam’s Teratorn live?

The remains of Merriam’s Teratorn have been found in various locations in North America, including California, southern Nevada, Arizona, and Florida.

The Rancho La Brea asphalt deposits in California have yielded a huge number of fossils, the remains of animals that became entombed in sticky tar between 8,000 and 38,000 years ago.

Bird fossils, rare elsewhere because they are so fragile, have been found in abundance at Rancho La Brea. This one rich deposit of fossils gives us an excellent idea of what birds lived in that corner of California all those millennia ago.

Some of these birds are still with us today, while others are only known from their bones. One of the most remarkable extinct birds from the deposits is Merriam’s teratorn, a relative of the colossal magnificent teratorn of South America and the living condor species. It is the most well-known of all the teratorn species, as the bones of more than 100 individuals have been recovered from Rancho La Brea.

Merriam’s teratorn was diminutive compared to the magnificent teratorn, but by today’s standards, it was a giant. With a wingspan of around 3.8 m and weighing in at about 15 kg, the closest comparable living bird is the Andean condor, one of the Merriam’s teratorn’s closest living relatives.

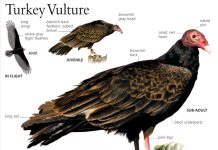

The Andean condor is a scavenging bird of prey that uses its immense wingspan to soar effortlessly on the thermals that rise into the air around the flanks of mountains as the sun warms the ground. High in the air, the condor can scan the ground below for its favorite food: carrion. When Merriam’s teratorn was initially described in 1909, it was assumed that the living bird was primarily a scavenger due to its similarities with the living condor.

Many decades later, paleontologists closely studied the skulls of this extinct bird and came to the conclusion that in life, Merriam’s teratorn was an active predator that spent a good deal of time on the ground, prowling areas of short vegetation for small mammals and other delicious morsels.

Other experts have compared the skull of Merriam’s teratorn to skulls from a number of other predatory birds, including living and extinct species. These comparisons indicate that the extinct giant may have been a specialist fish predator.

If this was the case, it may have had trouble plucking prey from the surface of the water with its feet, as they don’t seem to be up to the job of grasping a slippery fish. Some birds (e.g., frigate birds, Fregata sp., and some terns) pluck fish from the water with their beaks, and perhaps this is what Merriam’s teratorn did as it was gliding just above the surface of the water. If Merriam’s teratorn specialized in taking fish on the wing from inshore waters, then its abilities in the air must have been staggering.

With a wingspan approaching 4 meters, any wrong move just above the water’s surface must have ended in a very wet teratorn, and one that probably could not take off again. If this giant bird was able to pluck fish from the surface of calm, inshore waters, why have so many specimens been found in the asphalt deposits of Rancho La Brea? Birds of prey were drawn to Rancho La Brea for one thing: carrion.

Animals of every description met a slow and grisly end in these sticky tar pits, and the larger ones, in their struggles to free themselves, must have attracted predators from far and wide. Saber-tooth cats came to try their luck, as did dire wolves and a range of other large predators. Many of these also became trapped until the sticky goo was a banquet of dead and dying animals, just the sort of thing to appeal to scavengers.

Merriam’s teratorn and a host of other scavenging birds, including condors, eagles, and ravens, probably perched in trees near the edge of the tar pits, waiting for the final, futile struggles of a large mammal. With the poor animal still alive, the scavengers descended and perched on the hulking brute, tearing at the tar-matted hide with their sharp beaks.

Just like today, squabbles among scavenging animals were commonplace, and the teratorns probably jostled for space on the carcass until one of them lost its footing and ended up in the tar itself. In terms of behavior, the closest comparable living bird to Merriam’s teratorn may be the bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus ), a fish specialist with no qualms about eating carrion from a large carcass.

Perhaps Merriam’s teratorn, like the bald eagle, was primarily a fish eater but was occasionally drawn to the bounteous supply of carrion at Rancho La Brea, which, back then, was very close to the coastline. For hundreds of thousands of years, this immense bird graced the skies of North America, and it was undoubtedly known to Amerindians, who apparently hunted it.

Although Merriam’s teratorn may have had a similar lifestyle to the living bald eagle, it must have been heavily dependent on carrion, particularly the carcasses of large mammals, as its demise coincides with the disappearance of the large North American animals. With suitable carcasses becoming scarcer and scarcer and humans hunting them for food, the long-lived but slow-breeding Merriam’s teratorn was doomed, and sadly, it died out.

-

Merriam’s teratorn was the largest flying bird ever seen alive by humans, and it is very possible that this extinct giant could be the inspiration for the mythological thunderbird. In Amerindian stories, this enormous bird is said to cause thunder by flapping its wings, and its likeness is often seen surmounting totem poles. Perhaps the teratorn obtained immortality in the oral traditions and stories of the Amerindians as a folk memory.

-

A large, dead mammal can supply a large variety of scavenging animals with a huge amount of food, but there is always a pecking order at a carcass. Like the living lappet-faced vulture (Torgos tracheliotus), Merriam’s teratorn may have been the only scavenging bird capable of tearing through the thick skin and tough muscle of a large, fresh carcass. Just like today, the lesser scavengers may have had to wait until the teratorn ate its fill.

Scientific name: Teratornis merriami

Scientific classification:

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Aves

Order: Ciconiiformes

Family: Teratornithidae

Read More: Masked Owl