The Battle of Ox Hill, Chantilly took place on 31 August 1862, the day after the second battle of Bull Run. Chantilly, France, a town in the department of Oise, 25 miles north-northeast of Paris, on the Nonnette, is celebrated for its splendid chateau, built for the Due d’Aumale in 1876. It stands on the site of an older chateau that gained prominence under Anne de Montmorency. In 1632 it passed to the Conde family, but the majority of the house was demolished during the Revolution. The last prince of Conde bequeathed the domain to the Due d’Aumale in 1830.

The present building and domain, including fine grounds and gardens, an extensive forest, etc., were presented by the Duke to the French Institute in 1886. The chateau contains a valuable library and an impressive artwork collection. The place was celebrated for its lace manufacturing (Chantilly lace). It is an excellent horse racing and training center.

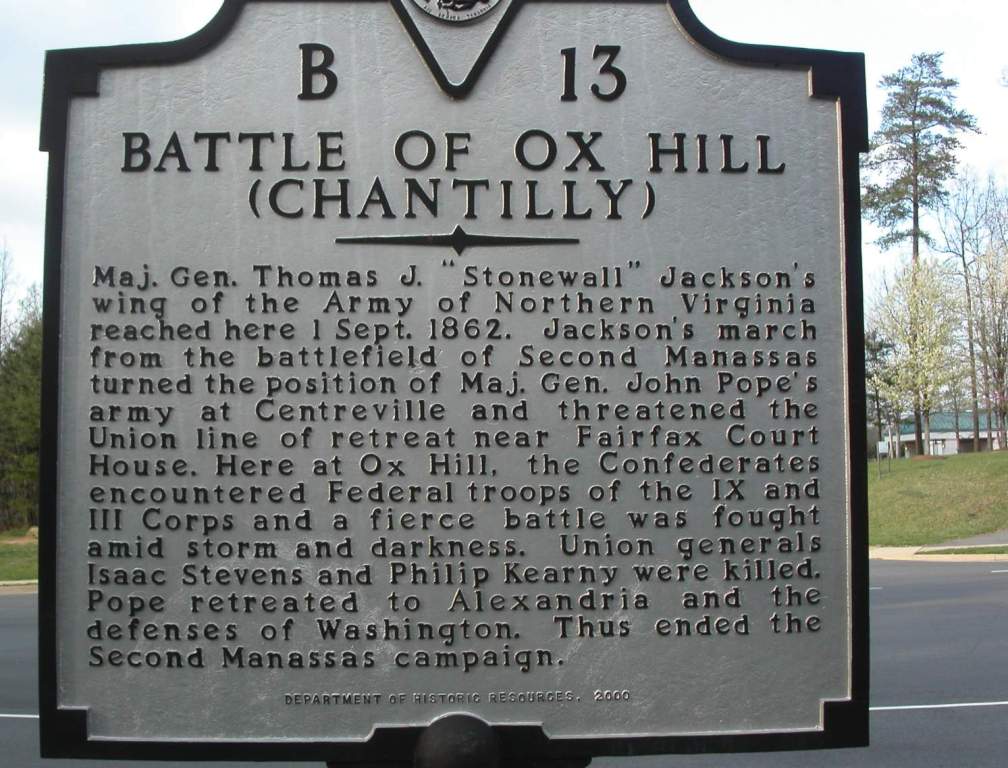

Gen. Lee marched his army through Sudley Ford around Pope’s right at Centreville, to seize Fairfax Court-House and interpose between Pope and Washington. Hence, at night Stonewall Jackson, who was in advance, bivouacked six miles west of Chantilly, on the Little River turnpike, Longstreet some distance in rear.

Next morning Gen. Stuart informed Jackson that at least a portion of the Union army was at Fairfax Court-House. Pope’s train passed on the road from Centreville to that place. Jackson moved cautiously toward Fairfax Court-House. On reaching Ox Hill, three miles east of Chantilly, Stuart informed Jackson that the Union forces were very strong on the road in front. Stonewall Jackson formed a line on Ox Hill Ridge, his artillery massed on the left of the road, his infantry on the right, extending towards Centreville Road. He had not completed his formation when he noticed an approaching force on Centreville Road. He strengthened his right and threw out skirmishers.

About 1 p.m. Pope, who heard Ackson’s advance toward his rear, sent Gen. I. Stevens with nine regiments, about 3,000 men, of Reno’s corps. They were to gain the road two miles east of Chantilly and hold Jackson in check until the army could be brought into position at Fairfax Court-House. Stevens moved from near Centreville across the fields, unexpectedly striking Jackson’s advancing skirmish line. He threw it out to his right and drove it back into the woods. Jackson then advanced a regiment from the woods, which was immediately driven back by Benjamin’s battery. General Isaac Stevens now formed an assault column, six regiments in three lines, and two regiments in a line.

At 4.30 p.m. he placed himself in the center of this column of 2,000 men, on open ground, and ordered it forward, Benjamin shelling the woods in front. Not a sight nor sound betrayed the presence of an enemy, until the advancing column, ascending a gentle slope, came to within 75 yards of the woods. From a worm fence bordering them, came a terrific volley from Branch’s brigade. It smote the column with remarkable effect, the men crashing down by the score. At first, it wavered, but quickly regained its strength, and as it resumed the fire, five color-bearers of the 79th New York, Stevens’ old regiment, were put down in succession.

The assault was halted, Stevens ran forward, seized the flag, and, calling upon his men to follow him, all rushed forward, routed Branch, and gained the fence. It left a bullet through Isaac Stevens’ brain and colors adorning his head and shoulders. The column pushed into the woods. At the moment of reaching the fence a sudden and terrific thunderstorm and fierce gale burst over the field. This blew the rain into the faces of both sides, impeding their movements and wetting their ammunition.

Stonewall Jackson brought up freshmen, and after a contest of more than an hour the six regiments were driven out of the woods and fell back to the point where they had formed, and on the right of where Birney’s brigade of Kearny’s division had come up. Meanwhile, three regiments of Reno’s command had been sent in on Stevens’ right, but only one of which, the 21st Massachusetts, became seriously engaged and was repulsed with substantial loss. Philip Kearny recently came up with a battery. He put in position and went to the right for a regiment to fill an interval on Birney’s right.

He met the 21st Massachusetts as it came out of the woods. He led it to the left when his attention was called to the fact that the Confederates advanced from the woods and through a cornfield on Bimey. He spurred his horse into the cornfield to reconnoiter, ran upon a skirmish line, saw his mistake, and turned to ride back when he was shot through the body and killed. A sharp encounter ensued between the 21st Massachusetts and the Confederates, which was ended by darkness; the regiment withdrew, the Confederates retired to the woods, and the battle was ended, neither side permanently gaining ground.

The other two brigades of Philip Kearny came up, and the ground was held until 3 in the morning. This is when Kearny’s and Reno’s men returned to Fairfax Court House after Pope’s army from Centreville passed. Pope returned to Washington, and Lee marched across the Potomac into Maryland. The Union loss at Chantilly was about 800; that of the Confederates was about 700. Philip Kearny and General Isaac Stevens died, and the Union army lost two of its finest officers.

Read More – Francis Scott Key – Author of the Text of U.S. National Anthem