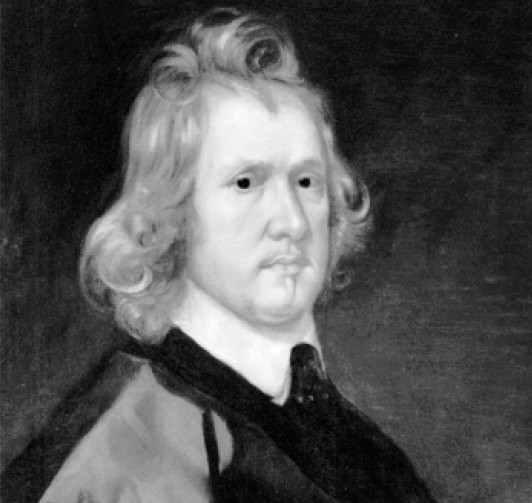

Oliver Cromwell is one of the most controversial figures in history. To some, he was a great man, to others, he was a tyrant. He was a politician, and a religious zealot, and deposed both the king and the Parliament before dying in 1658. There is no doubt, however, that he was one of the most influential figures in the history of Britain and in the establishment of European settlement in North America. In 1599, Cromwell was born in Huntingdon, England, and studied at Cambridge University nearby. A religious conversion experience led him to become a devout Puritan after earning his living through farming until around 1628.

Puritans were English Protestants who adhered strictly to Calvinist doctrine and discipline in order to simplify the Church of England. Cromwell was guided by a Puritan sense of dedication and an unswerving belief in his role as God’s chosen vessel throughout his life. His first election to Parliament was in 1628, but he didn’t really get involved in politics until 1640. At the center of the English Civil War was religion, which lifted Cromwell from obscurity. During the reign of Charles I (1625-1649), the Church of England began quarreling with the Puritans, and this division became more pronounced when laws were passed requiring Puritans to convert to Anglicanism.

Puritans began immigrating to America from Britain in 1630 as a result of this, settling mostly in the New England colonies. In 1642, an invading Scottish army besieged the unpopular Charles I, and the king was deprived of most of his royal power by Parliament, resulting in a war between the king and Parliament. One of the greatest generals in history, Cromwell rushed to defend Parliament despite his lack of military experience. He defeated the royalist forces (called Cavaliers) within two years after raising and training his own army.

The Roundheads he commanded eventually became the entire Parliamentary force. The New Model Army he created was a powerful fighting force that defeated Cavalier forces at Naseby in 1645. It was only a matter of time before Charles I was forced to surrender. During Charles I’s the reign, Parliament was divided over the proper form of government for England: the Presbyterians supported a constitutional monarchy under the king, while Cromwell and the army feared retribution. In the face of chaos, Cromwell decisively ended the impasse by defeating the Scottish army, purging the Parliament of 110 members, and bringing Charles I to trial. As a result of his conviction and execution, Charles I died in 1649.

Following the monarch’s death, Oliver Cromwell became the new monarch. He was happy to leave the governance of England to the members of Parliament who remained after the purge since he was the most powerful man in the country and the leader of the army. Despite their poor leadership, Cromwell was forced to disband them in 1653 by force. The only written constitution in Britain’s long history, the Instrument of Government, was created by him within five years of the deposal of the king and parliament. A permanent position of lord protector of the realm was granted to Cromwell. There were both great victories and great tragedies during Cromwell’s fifteen years in power.

Both his war against Holland (1652–54) and the seizure of Jamaica from Spain were important events in the development of the Atlantic economy. In 1649, he led an army to Ireland to settle a decade-old Catholic rebellion, and he routed the Irish armies at Wexford and Drogheda, slaughtering many surrendering troops and shipping them to Barbados. Despite Cromwell’s brief time in Ireland, the oath “The curse of Cromwell on you” continues to be repeated today even though he was only there for nine months. With his victory in 1651, he brought an end to the English Civil War by defeating a Scottish-royalist army.

As England’s virtual dictator during the Commonwealth, Cromwell ruled. With his increasing unpopularity among English citizens, who were craving a return to traditional government, he became increasingly unpopular. As a means of securing stability, Cromwell declined the title of king, instead offering his untrained son to serve as his heir apparent. Upon the elder Cromwell’s death in 1658, this proved disastrous, for his son was expelled. The monarchy was restored two years later when Parliament recalled the slain king’s son Charles II.

The historian John Buchan best summarized Cromwell’s life and legacy: A devotee of law, he was often forced to be lawless; a civilian to the core, he had to keep himself alive by the sword; with a passion for construction, his main task was to destroy … the most English of … figures, he spent his life in opposition to the majority of Englishmen; as a realist, he was forced to build the useless. Nevertheless, Cromwell’s influence was immense even in the New World.

After Charles II’s restoration in 1660, public reaction to Oliver Cromwell’s Puritan zeal, which helped Britain develop the Atlantic colonies, hastened the immigration of nonconformists to the United States. In addition, Cromwell sanctioned Charles I’s execution based on the claim that he had broken a covenant with the English people; Cromwell believed that a leader who breaches a covenant could be legitimately overthrown. A number of American colonies, such as Massachusetts and Connecticut, were founded based on this Puritan concept of covenantal government.

Read More – Hernando de Soto – Conquistador, Explorer, and Economist