Man has kept honey bees for thousands of years, research is only now revealing details of their complex lives, including the extraordinary dances’ used by workers to signal the whereabouts of food. Although people have kept honey bees for thousands of years, it was not until recently that these insects could be called domestic.

Throughout their association with man, honey bees have behaved exactly like their wild ancestors, man’s only contribution is to provide artificial homes in the form of various kinds of hives. Over the past twenty years, however, bee-keeping experts have perfected some delicate techniques for artificially inseminating female bees, and it is now possible to control their breeding.

Selecting insects with desirable features, such as high honey yield and a reduced tendency to sting, can modify the behavior of future honey bee populations. Of the many tiny animals that share the planet Earth with us,. However, there are only a few insects that people usually accept as beneficial.

Social life: the honey bee is a social insect, living in colonies of perhaps 80,000 individuals. Each colony is a huge family group headed by a fertilized female known as the queen. All the other bees are her offspring; most of them are subordinate females known as workers, but during the spring and summer there are also a few hundred males (drones), in the colony.

The queen does nothing but lay eggs, which she can produce at a rate of over one thousand per day. Except when she leaves on her marriage flight or in the middle of a swarm, she never leaves the nest. She has no pollen-gathering apparatus, and she cannot make wax.

She has a larger body than the workers because she produces a large number of eggs, but her brain is smaller since she does not have to carry out such complex tasks as the workers. Therefore, they later do all the nest-building as well as food collection and looking after the young ones. The sole function of the drones is to mate with the new queens.

Unlike the bumblebee colony, the honey bee colony is permanent, continuing from year to year. The population fluctuates a good deal during the year, with numbers increasing to a summer peak before falling again in autumn. Individual workers born in the spring and summer normally live for about a month.

While those emerging from their pupae in the autumn live through the winter. Bees emerging in late autumn may survive until June. The queens have much longer lives and normally head the colony for two or even three years.

Chemical messengers: The smooth running of the honey bee colony is controlled by various chemical’ messengers’ (pheromones), which are produced by the bees themselves and distributed throughout the population. They ensure that all the bees know what is going on and react accordingly. The queen produces several different pheromones in glands around her mouth and is picked up by the throng of workers who lick her, feed her, and surround her wherever she goes.

The workers continually feed each other and the larvae, and so the pheromones reach all members of the colony. One of the best-known groups of pheromones produced by the queen is the ‘queen substance. All is well as long as a certain level of queen substance is maintained throughout a colony, but if the level falls, the workers know that their queen is ailing, and they immediately set about rearing a replacement. Another important pheromone is produced by the larval bees. The workers pick up this message as they feed the brood and then pass it on to other bees so that it stimulates the foragers to go out and collect more food.

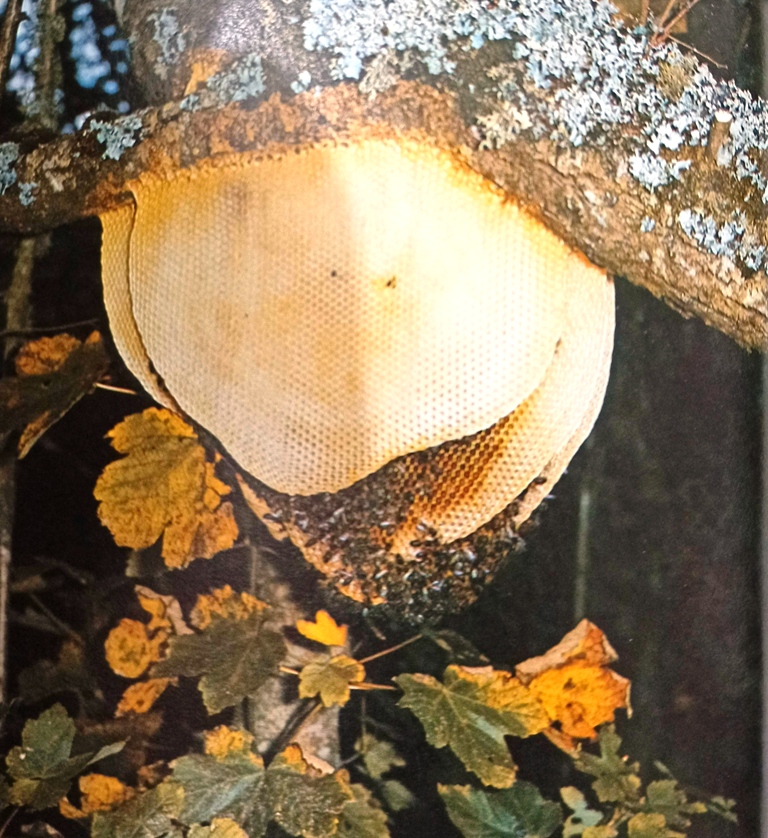

The nest and brood: The western honey bee occasionally builds its nest in the open, but the normal natural nesting site is in a hollow tree or cave. Within the nesting cavity, the honey bees build the nest entirely of wax produced on the bodies of the workers. It consists of several vertical sheets called combs, both sides of which are covered with hexagonal cells that are used for eggs, larvae, and pupae, as well as for storing pollen and honey.

The queen starts egg-laying in spring, laying one egg in each cell. The egg hatches in about three days and the larva then receive constant attention, being visited by workers every few minutes and receiving as many as 30 feeds a day. For the first two days, the larva is fed with secretions from glands around the workers’ mouths.

One secretion is a clear, protein-rich material known as brood- food, and the other is a white fatty material. Together, they are often called ‘royal jelly. Larvae destined to become new queens receive this food throughout the five days of larval development, but worker and drone larvae get a change of diet on the third day. The white secretion is withdrawn and replaced by honey and pollen, although brood food is still provided. The larvae are fully grown.

Life in the Comb

The honey bees’ nest is built with wax produced by the workers and consists of several vertical sheets called combs. Both sides of the combs are covered with six-sided cells that fit together perfectly. The hexagonal pattern means that no space is wasted. The nest is never empty, as shown here; workers are always about the large, acorn-shaped outer cells of the comb.

(1) Are queen cells. The larvae that hatch here receive special treatment, being fed on an ample supply of ‘royal jelly’ so they develop into queens. Other cells in the comb are used to store honey

(2) These cells are capped with wax. Nectar, still being processed into honey, is stored in uncapped cells

(3) While chemical changes proceed and much of the water content evaporates,. The queen bee roams over the combs and lays eggs in the empty cells. Fertilized eggs that produce workers are laid in smaller cells that are about 5.3–6.3 mm in diameter. Here are the worker larvae.

(4) Develop the worker larvae to become fully grown in about five days; at this stage, the cells are capped with wax.

(5) And the larvae pupate inside. The queen also lays unfertilized eggs that develop into drones. These eggs are laid in larger cells.

(6) Which are about 6-3–7 mm (in) across? Like the workers, the drones pupate inside capped cells.

(7) In five days, at this stage, the workers cap the cells with brownish wax, the larvae pupate inside and new workers emerge in about eight days.

Division of labor: Young bees normally start work by doing ‘household chores. The youngest are usually engaged in cleaning out brood cells, ready for more eggs. They actually control the population through the number of cells that they clean, for the queen will not lay in a dirty cell.

The glands around the workers’ mouths become active after about three days, and the bees can then feed the brood for about two weeks. The wax glands on the abdomen become active when the workers are between one and three weeks old. The bees can then build cells, although they continue to feed the brood as well.

They also begin to accept nectar from returning foragers and spend a lot of time converting it into honey. The next stage is for the workers to leave the nest and become foragers.

Honey: Forager bees collect pollen and nectar from flowers to feed the colony. Nectar the sugary liquid produced by flowers to attract bees for the purpose of pollination, is made into honey. On returning to the nest, the worker regurgitates the nectar and passes it to a ‘household’ bee.

This bee chews’ the blob of fluid in her mouthparts for about 20 minutes, during which time she adds enzymes that convert the sugar into glucose and fructose. The semi-processed nectar is then dumped into a cell for a while, during which time the chemical changes proceed and much of the water is evaporated. After a further period of manipulation in the bees’ mouthparts, the fluid, which is now true honey, is packed into cells and capped with wax.

New queens: When a queen becomes old, her pheromone production falls and the workers prepare to rear a new queen. They build a number of large, acorn-shaped cells on the edges of the comb.

The eggs laid in these cells are no different from those that produce workers, but the larvae are fed on an abundance of ‘royal jelly throughout their lives and thus become much larger than the less well-fed worker grubs. The first new queen to emerge from her cell normally tears open the other queen cells and kills their occupants.

She then goes off on her one and only marriage flight, during which she mates with several drones and receives enough sperm to fertilize the thousands of eggs she will lay over the next few years. The successful drones die soon after mating, but the queen returns to her nest to take over as ruler.

The old queen soon dies, and she may even be stung to death by her royal daughter. Unsuccessful drones also return to their nest and remain in the colony until the autumn, but they are then denied food and are evicted by the workers.

Swarming

Swarming is the bees’ method of starting a new colony. Overcrowding and a fall in the levels of the queen’s pheromones probably help to ‘trigger this. Prior to swarming, the workers build several queen cells and begin rearing new queens.

They also fill themselves with honey. Just before the new queens are due to emerge, the old queen flies off with a large group of workers. The swarm usually settles on a tree while scouts search for a suitable nest site. Returning scouts dance on the surface of the swarm.

They persuade other workers to inspect the sites and, after a good deal of ‘discussion’, the swarm accepts one of the sites and moves in. The honey that they carry from their old nest keeps them going until they settle down and begin foraging again. Meanwhile, one of the new queens takes over in the old nest; the bees have split into two completely separate colonies.

Read the Ebook The Healing Power of Honey.