The Onondagas (“People of the Hills”) controlled the heart of Iroquois territory in much of present-day upstate New York. They were hunters as well as agriculturalists, and their hunting territory ranged from modern-day Onondaga County as far north as Lake Ontario and as far south as the Chenango Forks. As the most centrally located of the original Iroquois Five Nations (the others were the Senecas, the Oneidas, the Cayugas, and the Mohawks), the Onondagas hosted its yearly councils under the Tree of the Great Peace.

They also provided the chief who presided over these gatherings. This key position rendered Onondaga’s political sentiments most crucial to how the confederation aligned itself with respect to European powers. The Onondagas acted as mediators of sorts in deliberations at the annual councils. If the elder “house” or brotherhood of the Senecas and the Mohawks could not agree with its junior counterparts among the Cayugas, the Oneidas, and later the Tuscaroras, then the Onondagas supplied the deciding vote. But they had no veto power in the event that the other native nations presented a united front.

The Onondagas also provide archivists for the confederation by maintaining its wampum belts and consequently sported the most chieftainships within the league. Their council house was one of the largest and most intricate Native American structures of its time. According to an Iroquois legend known as the Deganawidah (the Peacemaker) Epic, the peoples of the Five Nations frequently warred on one another until Hiawatha and Deganawidah promoted reconciliation. But an Onondaga chief and sorcerer, Tadadaho, rejected this message of peace and, in his resultant madness, grew misshapen with a bed of snakes for hair.

Hiawatha and Deganawidah subsequently cured Tadadaho with wampum beads, which symbolically spurred the creation of the Great League of Peace and Power. This alliance, which dated at least as far back as the 16th century, emphasized in-house stability and asserted authority over weaker native nations. The Onondagas participated in the Beaver Wars (1641–1701). During this period they warred with western nations such as the Hurons and the Eries over hunting rights and access to trade with Europeans and other native groups.

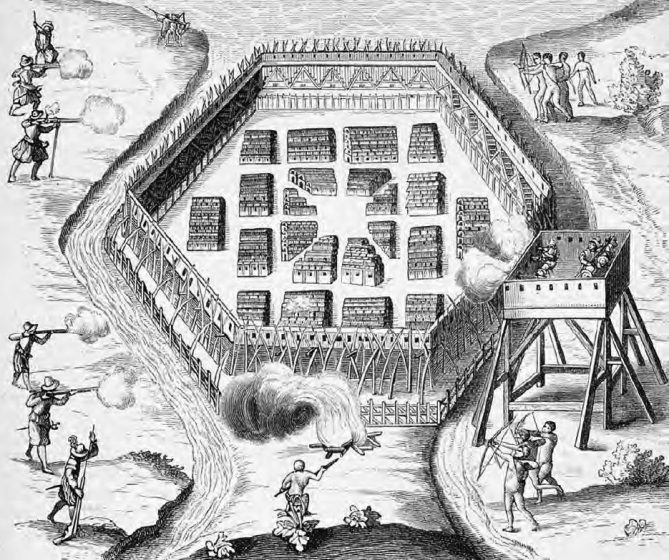

In addition, every so often relocating for better access to natural resources, the Onondagas generally confined themselves to inhabiting two large, fortified villages at a time. They employed fire to clear land for agriculture and forest underbrush for hunting. As with the rest of the league, they relied on adopting members of defeated nations to replenish their numbers. Some captives go through ritualistic torture and execution to grieve for lost loved ones.

The Hurons (allied with the French) and the Susquehannocks comprised the principal indigenous enemies of the Onondagas. During the 17th and 18th centuries, Protestants and Catholics proselytized between the Onondagas with partial success. The Jesuits established missions that proved short-lived because of dramatic shifts in support for the French. The Onondagas became factionalized throughout scheming among anglophiles, francophiles, and neutralists.

This constant intrigue influenced the diplomacy of the confederation and threatened to draw it into larger conflicts. Although neutral at first, by 1759 most Iroquois were supporting the British during the French and Indian War (1754–1763). The demise of New France in 1763 left the Six Nations (with the addition of the Tuscaroras in 1722) without its former position as the arbiter of the balance of power in North America. In the Proclamation of 1763, King George III established a limit for westward migration by American colonists.

Settlers largely ignored the rule that forbade expansion beyond the Appalachian 582 Opechancanough Mountains, and Onondaga landholdings came under increased pressure. The Treaty of Fort Stanwix (1768) reconfirmed the Great Covenant Chain through which the Iroquois dissuaded subsidiary tribes from attacking colonists. In 1776, when the American Revolutionary War was underway, both sides courted the league for a union. The Great Council opted to let each of the Six Nations decide for itself. The Senecas, the Mohawks, and the Cayugas joined the British, and the Oneidas and the Tuscaroras assisted the United States.

Accounts vary as to where a majority of the Onondagas stood on this question, but Patriot authorities regarded them as hostile. Pro-British Iroquois conducted raids alongside Loyalist Rangers in New York and in Pennsylvania. An American offensive in 1779 destroyed the Onondaga villages. The British loss of the thirteen colonies spelled disaster for the Iroquois Confederation as it was forced to cede most of its land in the Treaty of Paris (1783). The Onondagas then split between those who remained in New York and those who followed the Mohawk chief Joseph Brant to Canada.