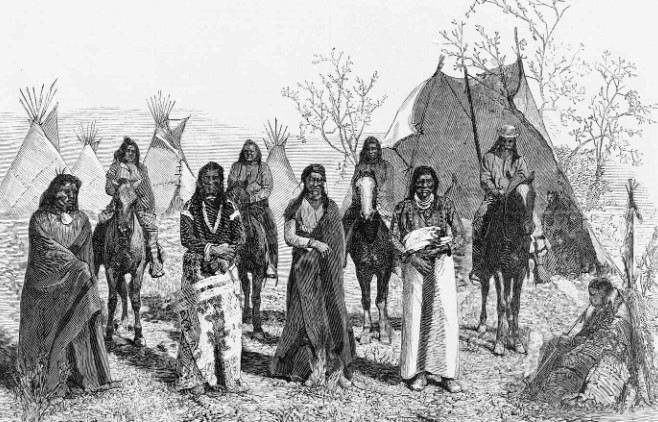

It is considered that the Bannock Tribe’s a branch of the PAIUTE that originated in the northern part of the province. Uto-Aztecan languages are shared by both peoples, as well as by the UTE and Shashones. It is pronounced BAN-uck. This tribe is categorized as GREAT BASIN INDIANS. They foraged and dug for any edible plant or animal in their harsh mountain and desert environment, including wild plants and animals, rodents, reptiles, and insects. Also common to them were the roots of the camas plant, which they shared with the PLATEAU INDIANS to their north.

Nomadic Bannock people occupied ancestral territories that are now part of southeastern Idaho and western Wyoming that were formerly occupied by the Bannock tribes. With the acquisition of horses in the early 1700s, they branched out into a broad area in which they occupied parts of Colorado, Utah, Montana, and Oregon.

There were many similarities between their way of life and that of the PLAINS INDIANS, including buffalo hunting and the use of tipis in their homes. Jim Bridger, a mountain man from the Bannock tribe, had opened up trade relations with his people in 1829 when he introduced them to goods. In spite of these advances, Bannock warriors preyed on migrants and miners traveling through their territory along the Oregon Trail in the following years.

The Fort Hall Reservation in present-day Idaho was established by the federal government in 1869 as a place for the Bannock and the northern branch of the Shoshone tribes to live after the Civil War when more federal troops could be deployed west to build new forts and pacify militant bands. There was strong resistance among the Bannocks to life on the reservation.

It was evident that their food rations on the reservation were meager, and tribal members continued to wander over a wide expanse of territory in search of the foods they had previously hunted and gathered for generations. During the early years of white settlement in the region, these traditional food staples of the Bannock were disrupted by the arrival of non-Indian hunters on the plains to the east, who were killing buffalo wholesale in the area. As a result, hogs belonging to white ranchers were also destroying the camas plants in the vicinity of Fort Boise, in the state of Idaho.

Along with their neighbors, the Northern Paiute, the Bannock revolted. 1878 was the year of the Bannock War. Two whites were wounded by a Bannock warrior, and the army was informed of the incident. A Bannock chief named Buffalo Horn led about 200 Bannock and Northern Paiute warriors. A volunteer patrol clashed with this war party in June. Following Buffalo Horn’s death, his followers headed west into Oregon to regroup with Paiute from the Malheur Reservation at Steens Mountain.

During the 1920s, the Paiute people were led by two Paiute chiefs: Egan and Oytes, both of whom were medicine men. The regular troops of the army rode out of Fort Boise in pursuit of the suspects. The NEZ PERCE were under the command of General Oliver O. Howard, who was responsible for tracking down the NEZ PERCE during their uprising the year before.

As a result of their efforts, the soldiers were able to catch up with the insurgents at Birch Creek on July 8 and dislodge them from the steep bluffs. Chief Egan and his warriors tried to hide out on the Umatilla reservation when they were under attack by the enemy. There was, however, a faction of the Umatilla people that sided with the whites.

After killing Egan, they led soldiers to Egan’s men and killed them as well. Despite his best efforts, Oytes was unable to evade capture until August, however, he eventually surrendered. After fleeing eastward to Wyoming, a group of Bannock escaped, but they were caught in September after trying to elude capture. Malheur Reservation was closed at the end of the Bannock War, which lasted for only a few days.

On their reservation in Washington state, the Paiute were settled among the YAKAMA on a reservation that belonged to them. In the past, the Bannock people were imprisoned at military posts for a period of time until they were finally allowed to return to their reservation in Idaho, where they now live.

There was another Indian war in Idaho that took place the same year, 1878, which was known as the Sheepeater War. As a result of their migration northward into the Salmon River Mountains of central Idaho, the Sheepeaters were Bannock and Shoshone people who hunted mountain sheep for their main source of food. It wasn’t long before they started raiding the settlers who were crowding their homeland.

The number of them was not large, perhaps only 50, but they proved to be a stubborn enemy for the army in the rugged highlands where they were stationed. There were two army patrols that they routed and another that they evaded. It was only in October that the army was able to wear them down with continuous tracking, so the Sheepeaters surrendered.

The Bannock and the Shoshone tribes accompanied them to the Fort Hall Reservation in Idaho where they were placed with their kin. A variety of traditional festivals are held every year by the Shoshone-Bannock Tribe of the Fort Hall Reservation, also called the Sho-Bans. These festivals include a weeklong celebration in August, several Sun Dances, and an all-Indian rodeo. Besides the Trading Post Complex, they also maintain a store called the Clothes Horse, as well as a bingo hall with high stakes, which is operated by them.

During the 1990s, the Sho-Bans began a campaign to stop the air pollution emanating from an elemental phosphorus plant located on the Fort Hall Reservation, which was a health hazard for the residents of the reservation. It is estimated that the federal government forced the plant to spend $80 million on improving its air quality in 2001. Read More – The History of the Arikara Tribe