Boring bivalves, as science unkindly names these extraordinary Shellfish use their hard shells to cut their way into rocks and wood. A bivalve is a mollusc a member of the same group as slugs and snails. But, unlike a snail, a bivalve has two shells known as valves. These are generally saucer-shaped and fit closely together, housing the mollusc in the cavity within.

Also unlike the snail, which uses its shell simply as a secure home, some bivalves have an additional use for their shell, for they function as excavating tools as well. It is thought that bivalves evolved as burrowing creatures. Normally they are working themselves into the sand by pushing with a single foot or manipulating their shells in a slow, shuffling movement.

Having established itself securely, the bivalve passes its life filtering its plank-tonic food from the surrounding water, drawing the water in, and passing it out through tubes known as siphons. In the course of time, bivalves have evolved other methods of obtaining a secure anchor age.

The common mussel, an example of a non-burrowing bivalve, anchors itself to rocks by tough, stringy secretions known as byssus threads. Here we look at a group to which science has given the unflattering name of ‘boring bivalves’, for they have the extraordinary ability to drill cavities in hard substrates such as rock and wood.

Beginning its life as an egg and then becoming a larva as most molluscs do, the typical boring bivalve emerges from the larval stage as a tiny ‘adult’ only a few millimeters long. The animal lodges itself in a crevice in its natural habitat-wood, limestone, clay shale, or other rocks.

It gains a purchase inside the crevice with its extensible foot, then, as it grows larger, its shell develops hard ridges or teeth, which it uses to grind out the cavity. Often the bivalve and the cavity continue to grow over a period of years.

The red-nose

The commonest rock-boring bivalve on the shores of the British Isles (and below shore level) is the red-nose (Hiatella arctica), recognizable by the pink tips of its siphons. It lives primarily as a nestler, attaching it by byssus threads in rock crannies.

But it may also bore a flask-shaped hollow in soft rock such as limestone or occasionally sandstone. The red-nose is a good example of a slow worker, for it bores less than one cubic centimeter a year, reaching a size, when fully grown, of 3 cm.

The flask-shell

A similar flask-shaped burrow is made by another bivalve, the flask- shell (Rocellaria dubia, formerly in the genus Gastrochaena). This species makes chalky tubes that protrude from the top of the burrow; they contain the siphons.

The tubes are formed from a secretion that flows from the siphons. The flask-shell bores into the sand, limestone, and sandstone at the bottom of the shore and below, and is found in the south and North-west of the British Isles. You can see it on the limestone blocks of the Plymouth breakwater in Devon.

The Piddocks

These are highly successful British Isles. Their shells are extremely hard, and have rows of fine teeth along the leading edge, facing into the burrow. Unlike the Nask-shell, the piddock is only partly enclosed within its shell, relying on the burrow to provide protection.

The common piddock (Pholas dactylus), which occurs on the south coast of England, has a shell of up to 15 cm (6in) long, the siphons extending as far again along the burrow. Other species include the oval piddock, the paper piddock, the white piddock, and the little piddock, which has a shell only 4 cm (1lin) long.

The American piddock (Petricola pholadiformis) is not a true piddock but a relative of the Venus shells. It was introduced into south-east England in the last century and is now common in the Thames estuary. Piddocks are unable to detect each other’s presence in the rock and consequently cannot avoid drilling into one another. If this happens, one piddock drills slowly but surely straight through the other.

The Shipworms

These notorious attackers of wooden vessels were a serious nuisance in the past when ships were made of wood, and continue to be a pest today, if to a lesser extent. They do not look like bivalves, for they are long and worm-like, with only a small shell at the burrowing end, which is, however, a superb cutting tool and particularly suitable for working in wood.

These animals can infest the timber of a boat’s hull or a breakwater in such numbers that it becomes full of holes and collapses. Shipworms are able to feed on the wood shavings produced when boring, in addition to their normal food-plankton.

A special appendix helps to digest the wood. Shipworms are relatively short-lived, surviving about a year, and many of them change sex from male to female. Fertilization may take place in the sea or, in some species, inside the female’s mantle cavity,

These common piddocks have drilled right through the rock (in this case a piece of fossil wood) and emerged through the underside. Normally this side is in contact with the sand, and the fossil has been turned over temporarily for photographing. You can see the fine rows of teeth along the leading edge of the shell, which acts as a file for boring deeper and deeper into the burrow. In some cases, you can also see the muscular foot of the animal inside the shell.

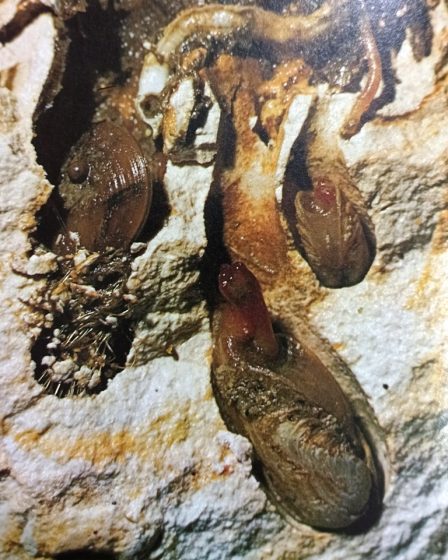

A rock-cut open to reveal three Hiatella bivalves in their burrows. These are named red-noses after the pink or red tips of the siphons.

Shipworms have eaten into this piece of driftwood and reduced it to a mere honeycomb. They can detect one another through the wood and so avoid collisions.

How the Shells Cut?

The chief mechanical method of cutting is grinding outwards Water is taken inside the mollusc and comes under pressure when muscles retracting the siphons contract. The pressure forces the shell valves to grind against the burrow walls. This is the main method used by the red-nose, and flask-shells use it too.

Twist-drilling – The sucker-like foot of flask shells, paddocks, and shipworms helps them grip rock and twist in the burrow like a drill. Using leverage Powerful adductor muscles of piddocks and shipworms pull the valves open and shut, exerting pressure across a fulcrum halfway along with the shell so that the valves rock in a see-saw action. This causes rows of hard, sharp teeth outside the shell to cut into the rock or wood.

Read More – The Avocet – A Rare British Bird / The Versatile Little Ringed Plovers

Product You May Interested

- Feel Emotional Freedom! Release Stress, Heal Your Heart, Master Your Mind

- 28 Day Keto Challenge

- Get Your Customs Keto Diet Plan

- A fascinating approach to wipe out anxiety disorders and cure in just weeks, to become Anxiety free, relaxed and happy.

- Flavor Pairing Ritual Supercharges Women’s Metabolisms

- The best Keto Diet Program

- Boost Your Energy, Immune System, Sexual Function, Strength & Athletic Performance

- Find Luxury & Designer Goods, Handbags & Clothes at or Below Wholesale

- Unlock your Hip Flexors, Gives you More Strength, Better Health and All-Day Energy.

- Cat Spraying No More – How to Stop Your Cat from Peeing Outside the Litter Box – Permanently.