Page Contents

The Little Ringed Plovers plumage pattern serves two contrasting purposes: during nesting it is camouflage, and yet in the display, it is vivid and eye-catching. Ringed plovers can be found on virtually every beach in Britain, at least for part of the year. They are selective in summer, choosing shingle, shell, and sandy beaches, but some disperse in autumn to join flocks of other waders on mudflats and estuaries.

Confusion of identity

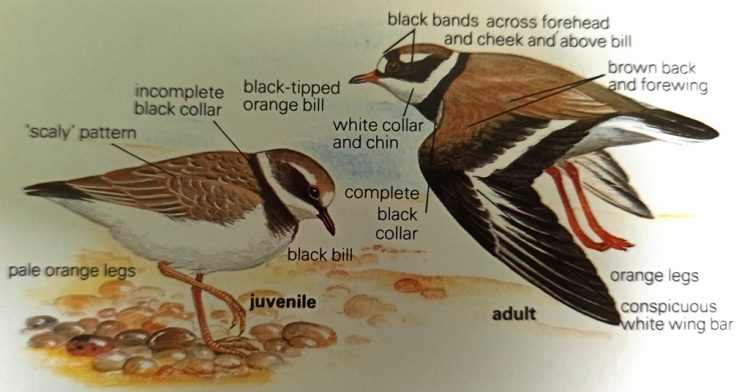

The only bird likely to be confused with the ringed plover is the little ringed plover. Both are aptly named since, especially in summer plumage, they have conspicuous black and white rings or collars on the head and neck. The difference in their size is only slight, so plumage features provide a much better way of distinguishing them.

The head pattern of both species is complicated. Each has a pale brown and black cap and a white forehead. Each is also black on the Front, behind, and around the eye, and there are white-collar and chin, and a second black “cellar below this.

However, of the two species, the ringed plover has more black on the crown, and it also lacks the yellow eye-ring and a white border at the back of the black forehead band, which are characteristic features of the little ringed plover. The ringed plover’s best distinguishing feature is a bold white wing bar, totally absent from its relative.

Such striking patterns prompt one to ask what purpose they serve. Recognition of other individuals of the same species is one obvious answer, but a study of the behavior of these birds shows that two other factors are important: camouflage and display. It might seem surprising that the same plumage should suffice to enable a bird to be either inconspicuous or conspicuous, but this is certainly true of the ringed plover.

Camouflage for Nesting

Effective camouflage is essential during the breeding season because ringed plovers nest on the ground on wide, open beaches. Shells and pebbles typically give a very varied pattern of stripes and curves in a wide range of colors and shades, and the ringed plover’s plumage blends perfectly into such a background.

Even sandy beaches usually have a scattering of seaweed and stones which the plover can mimic. The nest is a shallow depression, lined with small stones and odd bits of vegetation collected nearby. Predictably, the eggs are stone-colored, gray to buff in ground color, spotted, and blotched with black and gray.

They are laid one every day or two, four eggs being the usual clutch. The chosen site always has a good all-around view rocks and other obstacles are avoided so the incubating bird is able to watch for danger. On the approach of a predator, or perhaps someone walking along the beach, two alternative strategies are typically possible.

If the intruder is unlikely to approach closely, the incubating bird may sit tight and rely on its own camouflage color for protection. However, if the intruder is likely to come within a few yards of the nest, the better alternative is to leave the nest quietly, run some distance and then fly to safety.

The logic behind this course of action is that the nest and eggs are even more difficult to see that the incubating bird, and unless the intruder knows exactly where to look they are almost impossible to find. When the danger is past, incubation can be resumed.

Like other waders, ringed plovers have a very rapid flight, so it would be possible for them simply to wait and then fly to safety at the very last moment, but this sudden movement would almost certainly reveal the nest site and so jeopardize the eggs.

High Failure Rate

Incubation is shared more or less equally between the two sexes, changeovers occurring at least once each hour throughout the day and night. Off-duty birds usually fly off to feed or stand sentinel on a raised piece of ground nearby, ready to sound the alarm when necessary. Incubation lasts 23-25 days, typical for waders but about twice as long as the average garden bird.

Throughout this time the eggs must be kept warm, even if this means enduring Easter snowstorms in their bleak, windswept habitat. It has been calculated that 60% of ringed plovers’ nests are unsuccessful and perhaps as many as 87% of those in eastern England.

However, repeat clutches are laid and the majority of pairs probably raise at least one brood; some occasionally manage three. The very first eggs are laid in late March and the last in July. Ringed plovers are always careful to position their nests above the high tide mark, but tides.

However, the main cause of failure is predation, gulls, crows, foxes, dogs, and rats all being to blame. Here, too, we can include ourselves, for many a clutch of eggs has chilled when people have inadvertently stood or sat close to a nest for too long.

In cases such as these the camouflage of both birds and perhaps too effective, for the culprits are usually quite unaware of the problem. With ever-increasing tourist pressure on our beaches, birds are adapting to alternative sites, so their overall population is probably not declining.

The power station and oil refinery compounds have proved ideal, and some birds have nested on farmland by the coast. Further inland, particularly in northern England and Scotland, ringed plovers can be found in a variety of situations near water. Rivers, lakes, gravel pits, and reservoirs may all have suitable stony banks.

Read More – Grey-tailed Tattler (Tringa brevipes)

Displays for many occasions

Both male and female-ringed plovers frequently perform eye-catching mock-injury displays in defense of their young, drawing the predator away from the nest. The birds also defend their nesting and feeding territories from one another, though in this the male is typically more active.

Intruding ringed plovers are greeted with a marvelous threat display, in which the feathers on the breast, back, crown and underparts are increasingly erected, greatly accentuating the black and white head patterning. To complete the effect, the tail is fanned, and constant calling draws attention to the display.

Yet more displays are adopted during pair formation, mating and nesting. The easiest one of these to see is the male’s song flight. Throughout the breeding season, and particularly during the early stages of the nesting cycle, you can see him circling the territory, flapping his wings with deep, demonstrative strokes, and constantly uttering melodious, piping notes.

What Do Little Ringed Plovers Eat?

Ringed plovers feed primarily on terrestrial and coastal invertebrates, using a characteristic ‘ run-stop-peck-run-stop-peck’ technique. Even at night, they hunt by sight, watching carefully for their prey to move and then pouncing.

Marine polychaete worms, crustaceans, and mollusks comprise the main diet, though, at inland sites insects, spiders and even sticklebacks have been recorded.

On mudflats where food is plentiful, they often group together, but they never form such tight flocks as other waders like dunlin and knot. When the tide covers feeding areas, ringed plovers retreat to roosting sites that they choose for their safety from disturbance: salt marshes, beaches offshore islets, and farmland are all suitable.

Leap-frog migration

From extensive northern breeding areas, most of the world’s ringed plovers migrate long-distance to Africa. In doing so, they ‘leap-frog the ringed plovers of Britain and Ireland, some of which migrate ‘short-haul to the Spanish and French coasts, while others winter on the south coast of England, or even nearer their breeding sites.

The ringed plover is a sand and shingle nester, and the form of its nest is typical of all the wading birds: a simple scrape in the ground. The pointed eggs are laid in May, June, and July.

Identification Features

Ringed plover (Charadrius hiaticula), tends to like wader breeding on beaches. They are partial migrants, some birds wintering on mudflats and estuaries in the British Isles. Sexes alike and the normal length is 15 cm (6in).

The distraction display is performed in order to lead an intruder from the nest. The bird feigns injury and runs or shuffles along with one wing raised and the other dragging over the ground or (as here) folded.

A ringed plover is resting on the turf. There are two ways you can tell it is not a little ringed plover, even without seeing both birds together: this bird lacks a yellow eye-ring, and there is no white border at the back of the black band on the forehead.

The ringed plumage is good camouflage but also has a vivid visual effect when the bird adopts a demonstrative posture: thus it plays a part in the highly developed display behavior of the species.

Read More – The Avocet – A Rare British Bird

Product You May Interested

- Feel Emotional Freedom! Release Stress, Heal Your Heart, Master Your Mind

- 28 Day Keto Challenge

- Get Your Customs Keto Diet Plan

- A fascinating approach to wipe out anxiety disorders and cure in just weeks, to become Anxiety free, relaxed and happy.