Wolf shooting in Russia is a fascinating ancient game.

In Russia, the wolf is everyone’s enemy. It is therefore the business of everyone to kill him whenever and wherever he meets. This is so long as his killing can be carried out without danger. There are many ways to do this. The wolf is not dangerous alone, but in groups of two or three, even four or five. It is only when, half-starved and frantic with hunger, he assembles in tents and scores to ravage the country that he may be a source of real peril to human beings, and this—despite many excellent and exciting tales of wolf-packs and pursued human beings—is a matter of rare occurrence, since wolves are not so numerous that a pack of a hundred or so can easily get together to attack human beings.

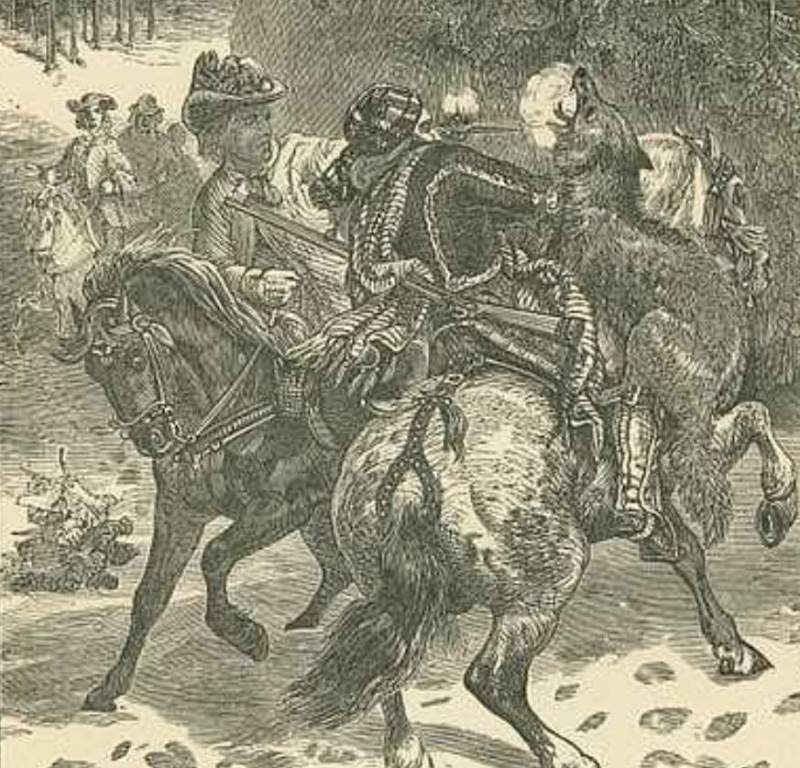

In the south of Russia, wolves are hunted with dogs of a special breed. Men on horseback follow the hunt, and the quarry is not, as a rule, pulled down by hounds but shot by the guns of mounted sportsmen. In the north of Russia, wolves are not hunted with dogs, their destruction being brought about, as a rule, in one of three ways: either by battue, by decoy, or by a peculiar method of discovering and killing them, which may be described as the pig-squeaking method.

To consider the first of these three ways of ridding the country of a pest, it may be said that a wolf may be started, unexpectedly, at any hare-battue in autumn, for until the snow comes, to give unfailing evidence of his presence, he may, of course, appear anywhere. For this reason, if he is being beaten while shooting, it is good to have a slug cartridge handy for his benefit. Should he, as he occasionally does, suddenly find himself among the hares and the black game?

On this subject, it may be further suggested that a ball cartridge in another pocket is not amiss on such occasions, for during the autumn battles around St. Petersburg, it has happened before now that a bear has suddenly darted out and away in response to the beaters’ yells. But a real wolf battle is different. This had been carefully planned, perhaps a month beforehand. Animal carcasses have been laid down to attract any wolves wandering in the neighborhood. However, wolves are no longer very numerous. Perhaps two or three weeks passed without the odor. This is strong enough to sicken a human being at a quarter-mile range, reaching the nostrils of a single wanderer. But suppose the wolves have smelled the feast and arrived in force—four or five.

After they have supped on the malodorous carcass once or twice, they should, if need be, be coaxed to remain around the place. This is done by placing new decoys close to the original spot. The keeper has his eye upon the party, and while they lie surfeited and sleepy with the carrion provided for them, he first sends a telegram (if the quaint old sporting books of three centuries back show how frequently powerful greyhounds were used to overtake and tackle wolves, which the ordinary track-hounds had roused from their lairs).

The ordinary greyhound, used for hare hunting, is too light for rough work against dangerous prey, and in most countries, the few remaining wolves have retired to wooded and rocky cliffs that greyhounds cannot reach. While wolves are found on large plains, like those in Russia, Siberia, and many parts of western North America, greyhounds are specially adapted for chasing them.

Currently, there is a great deal of wolf-coursing in both America and Russia, though conditions are very different in each country. Only the wealthiest nobles enjoy wolf shooting in Russia, which is considered a pure, simple sport. Occasionally in the United States, army officers or ranchers practice wolf shooting, but most commonly by people seeking to exterminate wolves for bounty or to protect cattle heads. Moreover, in the United States, the settlements continue to increase, the wolves decrease, and the sport has become even more evanescent. It has never assumed any kind of fixity.

In both places, special dogs are bred for this purpose. In Russia, these are the borzois, or long-haired greyhounds, a type that has been around for centuries. In America, a few men, during the last thirty or forty years, have bred tall greyhounds, both smooth- and rough-coated, producing a type that shows signs of reversion to the old Irish wolfhound: dogs weighing a hundred pounds, of remarkable power, and of a reckless and savage temper. The professional hunters, however, draft into their packs any animal that can run fast and fight hard, and their so-called greyhounds are often of the mongrel breed.

There is a science behind the sport of wolf shooting in Russia. The princes and wealthy landowners who participate in it are meticulously meticulous about the smallest detail. Not only do they follow wolves in the open, but they also capture them and let them out before the dogs. This is how hares are thrown out at ordinary coursing matches. The hunter follows his hounds on horseback. Two, three, or four dogs usually run together, and they are not expected to kill the wolf but merely to hold him. As soon as possible after he is thrown, the huntsman leaps to the ground, forces the short handle of his riding whip between the beast’s jaws, and then binds them tightly together with the long thong.

Both skill and coolness are needed, both for dogs and men. The borzois can readily overtake and master-groom wolves, but a full-grown dog-wolf, in proper trim, will usually gallop away from them and outfight any reasonable number. A good many borzois have been imported into America, but when compared against our wolves, they have not, as a rule, done as well as the exemplified home-bred dogs.

In America, the only place where I have had a chance to participate in the sport, it is, of course, conducted in a much more rough-and-ready manner. For fifty years, United States Army officers on the vast plains have used greyhounds to chase jackrabbits, foxes, coyotes, and occasionally antelopes. Now and then, those dogs that had been trained on coyotes were used against big wolves. However, it was only during the last few decades that the sport became common.

There are now, however, many men who follow it in Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, and western North Dakota. There is a pack near my ranch on the Little Missouri that has a record of several hundred wolves to its credit. The owner is a professional Wolfer, and his dogs represent every kind of pure blood and half-blood greyhound; but they are a wicked, hard-biting crew, and as they are usually hunted eight or ten together, they will, unlike the borzois, tear even the biggest wolf literally to pieces without assistance from the hunter.

Numerous casualties occur in the pack, for a wolf is a desperate fighter, and the sound and sight of worry are quite blood-curdling. The Sun River, in Western Montana, was once a famous place for its wolfhounds, and there was another celebrated pack near Fort Benton. However, it has been eight years since I was in either neighborhood, and time marches fast in the west. My own experiences have usually been with scratch packs, to which I have occasionally contributed a dog or two myself. Ordinarily, these packs contained nothing but greyhounds, either smooth- or rough-coated, but in one of them there were two huge fighting dogs of mixed ancestry, which could not keep up with the greyhounds but did most of the killing when their lighter-footed friends stopped the quarry.

The greyhounds we usually hunted had not been specially trained for the work and were not bred for the purpose. Instead, they served an apprenticeship as coyote hunters. In consequence, they were not capable of killing the wolf without assistance. They usually stopped him by snapping at his hams. They would then form a ring he could not break. If he broke, they would overhaul him immediately and bring him to a standstill. The hunters either shot him or roped him.

I doubt if the sport, even when carried out more rationally, could afford more fun than these helter-skelter scurries over the plains gave us. We generally started for the hunting grounds very early, riding across the country in a widely spread line of dogs and men. If we encountered a wolf, we simply shot at him as hard as we could. Young wolves, or those that had not attained their full strength, were readily overtaken, and the pack would handle a small she-wolf quite readily.

A big dog-wolf, or even a full-grown and powerful bitch-wolf, presented an altogether different problem. As a result, we found them after they gorged themselves on a colt or calf. Under such conditions, if the dogs had an excellent start, they would run into the wolf and hold him. However, if the large wolf in a well-prepared running trim kept ahead of them for half a mile or so, his superior strength and endurance were apparent, and he gradually drew away.

Of course, the pack composed of specially trained and specially bred greyhounds of superior size and power made a good showing. Under favorable circumstances, three or four of these dogs readily overtook and killed the largest wolf, rushing in together and seizing by the throat. The risk to the pack was so significant, however, and the dogs were so frequently killed or crippled in the fight that the hunter always endeavored to keep as close as possible, and on his arrival, he ended the contest with a knife-thrust.

In running, the dogs usually had an advantage because they were so apt to find the wolf near a carcass from which it had just made a hearty meal. Often, the dogs are transported to the battle field. Their dashing courage and ferocious fighting capacity were marvelous. In this respect, I never saw much difference between the smooth-haired and the wire-haired, or Scotch deer-hound, types, while the smooth-breed were generally faster.

Read more: Is the Tarpan Extinct?