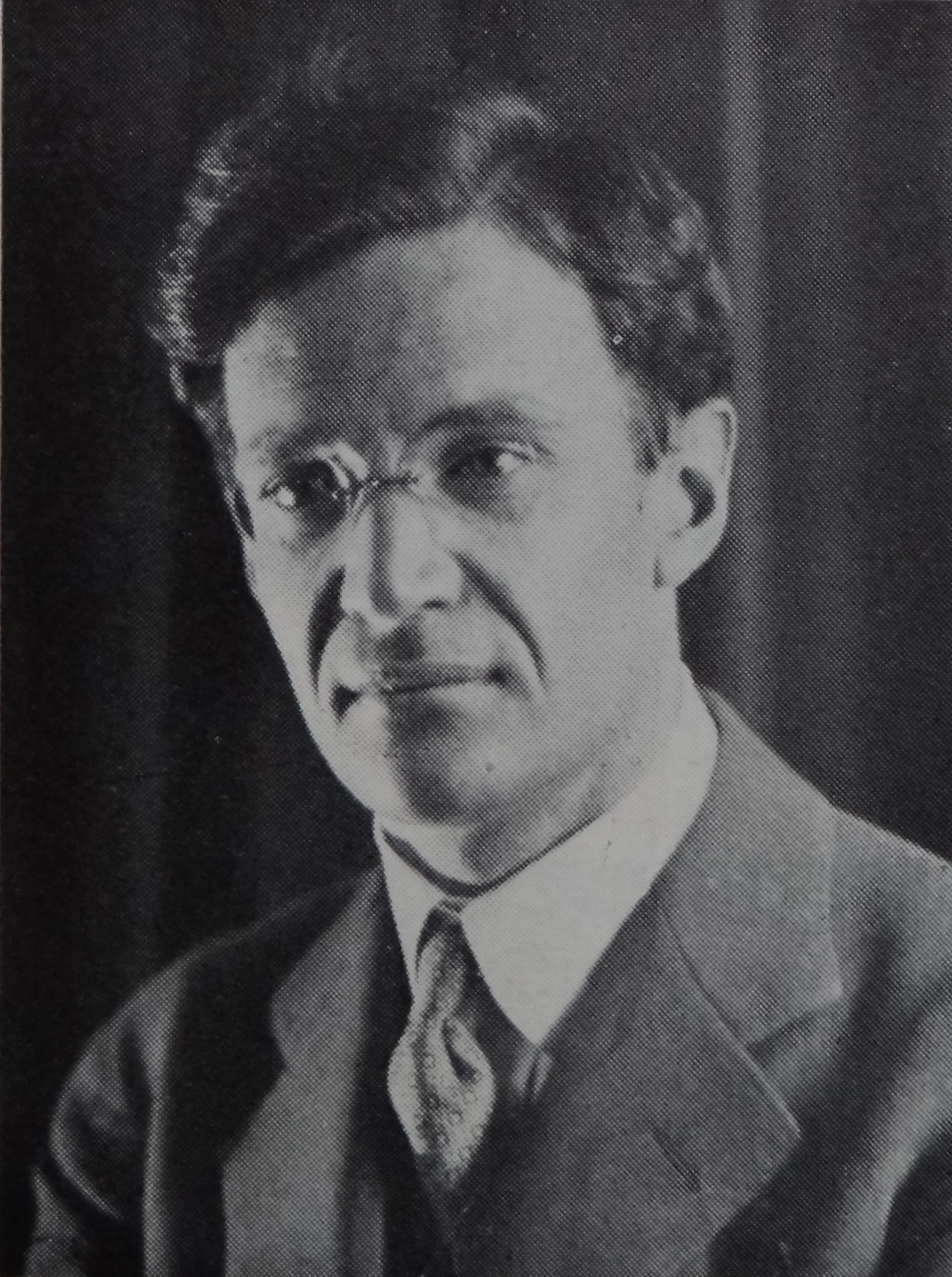

Mowrer Edgar Ansel is regarded as the dean of American foreign correspondents. Mowrer was an author, journalist, and lecturer. He was an outspoken proponent of a vigorous foreign policy on the part of the United States and its allies. Mowrer began his career in journalism as a war correspondent for the Chicago Daily News in 1914. He was its chief foreign correspondent for more than twenty years.

Having occupied a ringside seat at many of the major events of recent history, Mowrer came to know several of its leaders personally; he was one of the first to recognize the bellicose intentions of Mussolini, Hitler, and the Japanese. In 1933, he received the Pulitzer Prize as the best foreign correspondent. Mowrer has written ten books dealing with political affairs and many articles for national magazines.

His political analyses in a widely read column for the McClure Newspaper Syndicate: Edgar Ansel Mowrer was born in Bloomington, Illinois, on March 8, 1892. He was the younger of two sons of Rufus Mowrer, a businessman, and Xell (Scott) Mowrer. His brother, Paul Scott Mowrer, who won the Pulitzer Prize as the best foreign correspondent in 1929, served as editor of the Chicago Daily News from 1935 to 1944.

He has written six volumes of poetry. Edgar Ansel Mowrer attended Hyde Park High School in Chicago, where he was active in tennis, basketball, and golf and edited the school annually. After graduating from high school in 1909, he entered the University of Chicago but interrupted his studies there to attend the University of Paris for a year.

Upon returning to the United States, he studied philosophy and literature at the University of Michigan, edited the university’s monthly magazine, The Painted Window, and shared the poetry prize. Mowrer received a B.A. degree in 1913. Following his graduation from the University of Michigan, Mowrer returned to Paris. His brother was a correspondent for the Chicago Daily News.

At the time, he had no intention of becoming a journalist but considered entering the legal profession, teaching philosophy, or becoming a literary critic. In Paris, he lived for a time on the Left Bank and wrote essays and critical studies on philosophy and literature, which were published in “the more emancipated English reviews.”

With the outbreak of World War I, Mowrer was pressed into service at the Paris office of the Chicago Daily News. When his brother was sent to cover the Battle of the Marne, during his brother’s absence, he filed dispatches, which his brother subsequently approved, and he thus stumbled into a career as a journalist.

Assigned by his brother to bicycle to the battlefields around Meaux, Mowrer later covered the war in western Flanders. He was arrested in Ypres on charges of espionage, deported to England, and again arrested upon his return to Belgium. After his release, he continued as a war correspondent, reporting on the desolation, starvation, and cruelty he saw around him.

In May 1915, he was assigned to the Rome office of the Chicago Daily News, and there he interviewed Benito Mussolini, then a socialist, who was urging Italy to enter the war on the side of the Allies. After his marriage in London in February 1916, Mowrer returned with his wife to Italy, where he covered the battlefronts and witnessed the Italian defeat at Caporetto in 1917.

For a time, he was seriously ill with Spanish influenza. His first book, Immortal Italy (Appleton, 1922), was praised by C. E. Merriam in the Political Science Quarterly (December 1922) as “a very readable and useful contribution to the understanding of Italy that is in the making.” Transferred to Berlin in 1923, Mowrer spent the next decade in Germany.

His second book, This American World (Sears, 1928), in which he predicted that the United States would ultimately attain a world empire, was designated by Leon Whipple in Survey (June 1, 1928) as “the best book of the year, in philosophical depth, in range of synthesis, and in pure excellence of language.” During this period, he also wrote The Future of Politics (Routledge, 1930).

Mowrer Edgar Ansel predicted the downfall of the Weimar Republic in his book Germany Puts the Clock Back (Morrow, 1932; revised edition, 1939), which was first published shortly before Adolf Hitler came to power and was subsequently banned in Germany.

Joseph Shaplen described the book in the New York Times (January 8, 1933) as “a genuine contribution to modern history, a keen, incisive, authoritative and extremely well-written account of what has happened in Germany since the war and why.”‘

As president of the Foreign Press Association in Germany, Mowrer defied the Nazis when they threatened to expel reporters who filed dispatches unfriendly to the new regime, and he refused to accede to Nazi demands that he resign his post.

After the Nazis imprisoned Goldmann, a Jewish correspondent for the Vienna Neue Freie Presse who was a friend of his, Mowrer offered to resign the presidency of the Foreign Press Association in exchange for Goldmann’s freedom. This was arranged, and when Mowrer reluctantly left Germany on orders from the Chicago Daily News, his colleagues gave him a silver bowl inscribed with “gallant fighter for the liberty of the press.”

Upon his return to the United States, Mowrer lectured for the first time to American audiences, warning them of the burgeoning power of fascism. Although he had expected to be sent to Tokyo, Mowrer was assigned in January 1934 to replace his brother as chief of the Paris bureau of the Chicago Daily News.

From this vantage point, he covered the events that led to the outbreak of World War II, and he acquired a growing distrust of plebiscites and treaties. In 1936, he covered the beginning of the civil war in Spain and visited the Soviet Union to report on the adoption of the new Soviet constitution.

Upon his return to France, he witnessed the fall of the Popular Front government headed by his friend Leon Blum. He visited China for a few months in 1938 to gather material for his book, The Dragon Wakes. A Report from China (Morrow, 1939) and then returned to Paris, where he remained until the fall of France in June 1940.

Assigned in August 1940 to Washington, D.C., as a correspondent for the Chicago Daily News, Mowrer collaborated with William J. Donovan on a series of articles on fifth-column activities in Europe. Several trips to the Far East in the next two years resulted in the book Global War: An Atlas of World Strategy (McClelland, 1942), which he wrote in cooperation with Marthe Rajchman.

From 1941 to 1943, he served as deputy director of the Office of Facts and Figures in the Office of War Information and broadcast news analyses from his post in Washington. In his postwar book The Nightmare of American Foreign Policy (Knopf, 1948), Mowrer criticized the foreign policy of the United States since 1918.

He expressed pessimism about the American love of the status quo and warned that the United States must choose between “world leadership and rapid decline.” He advocated a voluntary federation, strong enough to keep world order by the enforcement of world law. He maintained that the United Nations, which he described as “an unfinished bridge leading nowhere,” was inadequate to undertake this task.

-

W. Fox, writing in the New York Times (October 31, 1948), called the book “incomparably the best study of American foreign policy for this period that has yet been written.” Pursuing his ideas on international organization further in Challenge and Decision:

A Program for the Times of Crisis Ahead (McGraw, 1950), Mowrer urged the United States to take the lead in forming a “peace coalition” and the ultimate federation of non-Communist countries, with the aim of weakening the “expansionist bloc.” M. S. Watson noted in the Saturday Review of Literature (December 9, 1950) that Mowrer’s program resembled that of the United World Federalists.

In his A Good Time to be Alive (Duell, 1959), a collection of articles he wrote for the Saturday Review, Zionist Quarterly, Western World, and the New Leader, Mowrer sun-eyed the impact of world affairs upon the United States.

He suggested that Soviet successes were compelling Western peoples to “pull themselves together in a real effort to survive as free men,” and concluded that America’s pioneer spirit was “still warm beneath the ashes of self-indulgence.” Mowrer’s most recent book, An End to Make-Believe (Duell, 1961), analyzes the history of the cold war and its meaning to Americans.

In it, he contrasts what he calls the “fanatical ambition of international Communism with the unshakeable complacency of most Americans,” and maintains that in “the sinister game of international poker forced on us by Moscow and Peiping” the West still “holds the aces” but needs “bolder, better players.”

Discussing the hazards of overpopulation in the Saturday Review (December 8, 1956) Mowrer expressed his view that the soaring birth rate leads to increasing constraint, conformity, and loss of freedom and the destruction of natural beauty. A champion of what he calls the “Open Universe” theory, Mowrer wrote in the Saturday Review (April 19, 1958) that from an early age he “craved wildness the quality of the unpredictability that defies control.”

He maintains that the modern scientists’ unified field theory constitutes “a painful shrinkage of the area of surprising anticipation.” From 1957 to 1960 Mowrer was editor-in-chief for North America of Western World. An independent, international monthly, published in English and French editions and “dedicated to the preserving and strengthening of the Atlantic community of nations.”

Three times a week Mowrer analyzes world affairs in a column for the McClure Newspaper Syndicate. His columns appear in newspapers in the United States, Latin America, France, Belgium, and the Philippines. Mowrer has served as a consultant to Radio Free Europe and he is a trustee of Freedom House.

He was awarded the 1933 Pulitzer Prize for his reporting from Germany. Then he received the ribbon of the Legion of Honor from the French government. Edgar Ansel Mowrer and Lilian May Thomson were married on February 10, 1916. Mrs. Mowrer, a native of England, is the author of several books, including Journalist’s Wife (Morrow, 1937; Grosset, 1940).

They have one daughter, Diana Jane. Mowrer is five feet nine inches tall, weighs 150 pounds, and has gray hair and brown eyes. He belongs to the Century Club in New York and to the Adventurers Club in Chicago, as well as to professional organizations.

He has no religious or political affiliations. Formerly fond of skiing and canoeing, Mowrer now lists his favorite recreations as walking, mountain climbing, and chess. In 1969, Mowrer decided to move to Wonalancet, New Hampshire, and wrote a lengthy column for The Union Leader until 1976. He died on March 2, 1977, at the age of 84.

Ted Bundy – The Worst Serial Killer / John Paul Jones – First Captain in the History of American Navy