A fascinating history of Circus, actually a word from Latin without change, means “circle”. The Romans used it to indicate the place in each city where chariot races, gladiatorial contests, and feats of skill were held. The circus building in Roman times was without a roof and rectangular in shape, except that one short side formed a half-circle; on both sides and on the semicircular end were the seats of the spectators, rising gradually one above another, like steps.

The largest Rome building was the Circus Maximus, 1,875 feet long and 625 feet wide. Pliny said it was capable of containing 260,000 spectators. At present, however, few vestiges of it remain, and the circus of Caracalla is in excellent preservation. Growing to greatness through the conquest of other peoples, the Romans of 2,500 years ago (and for 10 centuries later) encouraged all forms of pleasure, which would develop to its highest pitch the fighting instinct in their soldiery.

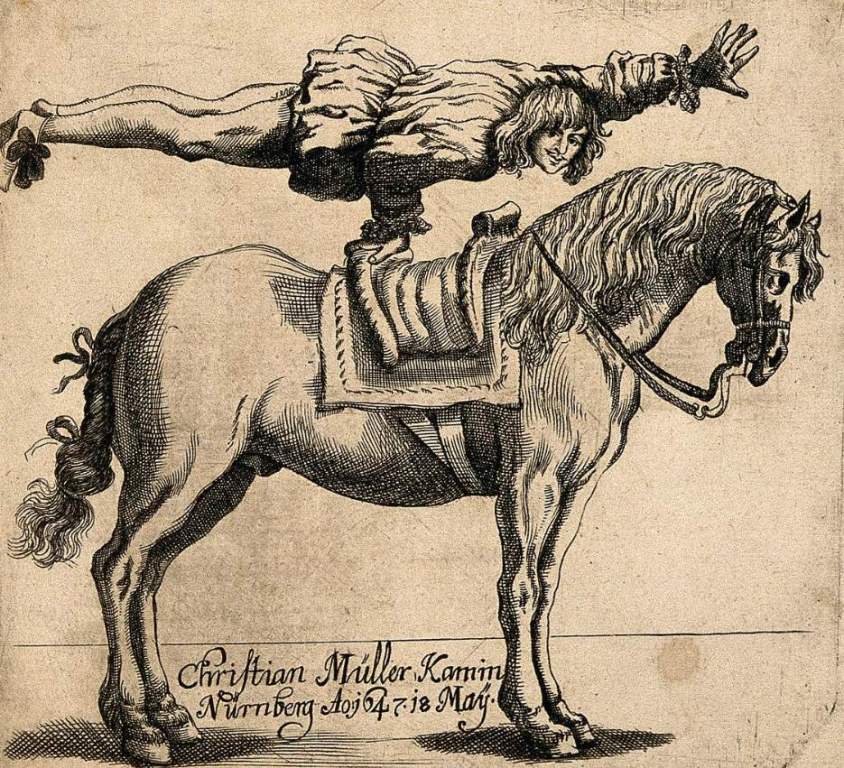

Circus games included chariot races, a favorite sport of the Romans; athletic contests; the Trojan games, contests on horseback; and combats with wild beasts, in which beasts fought beasts or beasts with men (either criminals or volunteers). The victors received valuable prizes, and the honors were exceptional. In Rome’s decadence came a decline in the circus. It was characterized by revolting spectacles, in which Christians or others temporarily hated by the government were given over to wild beasts or crucified. Julius Caesar dug ditches around the circus and filled them with water.

This served the double purpose of protecting spectators from the sudden swerving of a chariot or the spring of a tiger. It also made possible feats of skill on the water. Most of the vessels then were propelled entirely by banks of oars, and Caesar held rowing races, swimming races, etc. Most of our grotesque picnic games, like swimming in a barrel or running in a sack, are relics of his fertile inventions to please his restless, turbulent people. There was no charge to see these entertainments. As a rule, the circus was used as a pacifier by the emperor.

America has taken the lead in reproducing Circus Maximus. This is probably because the American people are similar in their strenuous, contest-loving, restless disposition. It was his acute perception of this disposition in his countrymen that led Phineas Taylor Barnum, a Connecticut Yankee, to devote his life to entertaining his countrymen by giving them a real circus. He started the American Museum at the corner of Broadway and Ann Street, New York, a site now occupied by the 20-story St. Paul Building. Soon he began to exploit all kinds of freaks and curious individuals, with “Torn Thumb” and other dwarfs among his features. He saw the public’s greed for odd, grotesque things.

The public loves to be humbled, which was one of his frequent declarations. Yet Barnum always gave the people what he promised and soon had on the road the beginning of what has since become perhaps the largest “show” on earth. Since Barnum’s death, the circus has been directed by Mr. Bailey, his partner, for some years before that event. Barnum & Bailey’s circus and menagerie cannot be described. It is usually formed by making three immense rings and three different performances simultaneously.

With 1,000 performing horses, 2,000 horses to haul the tents and equipment from town to town, hundreds of wild beasts in a menagerie, 500 performers, bare-back riders (both sexes), clowns, aerialists, tumblers, etc., 1,200 other employees to care for the animals and erect the tents (seating 25,000), put up show-bills, etc., advance agents, cashiers, managers, and other attaches, bringing up the total to about 3,000 people employed during the season, the conducting of such a circus requires consummate ability and great pecuniary resources. A dozen trains of cars are necessary to carry this exhibition, and a whole ship is used when it visits Europe, as it often does, successfully.

The capital invested in this and other circuses in America is enormous, ranging from $100,000,000. There are 8 or 10 large circuses and 20 more smaller ones operating in America (1903). Barnum fixed the admission price for common seats at 50 cents, and this has never changed since. The better seats, near the center, are $1.00. These seats correspond to those of the Roman emperor and his court in the old Circus Maximus. Vast crowds attend these exhibitions, particularly in the rural districts, where “circus day” is as much of a holiday as the 4th of July.

In most cases, at the end of the season (about October), the circus proprietors earn 100 percent or more unless there is a continuous rainy season. Since 1890, an American circus form has been worthy of mention. This is a reproduction of the habits and customs of the “cowboy” and pioneers of our own western plains. The exhibition is called a “Wild West” show. It was originated by William F. Cody, known as “Buffalo Bill”.

He was a former government scout and knew many Indian tribes. With “Nate” Salisbury, he organized an exhibition of frontier and Indian life that rivals Barnum & Bailey’s interest and profit. He has a hundred western cattle herders, who illustrate the perfect horsemanship of the plains; he has many American Indians from a score of tribes, who give their war dances and weird chants; he has Mexican lariat-throwers, who perform wonderful feats with swirling rope; he has trough riders from various lands.

As a whole, this show appeals powerfully to both young and old Americans. Several less prominent “Wild Wests” have also been organized. Some American college youth have recently revived interest in the ancient Greek Olympic games. A delegation of them traveled to Athens in 1902 to compete with the modern Greeks and other national champions. These efforts may eventually rehabilitate the Hippodrome and Circus Maximus in the land that gave them birth.

Read More: James Holman – A British Blind Traveler